An eloquent write-up about Lena Hendry’s case (one of Pusat Rakyat LB’s strategic litigation cases), by Charlotte Kong, intern of Pusat Rakyat LB.

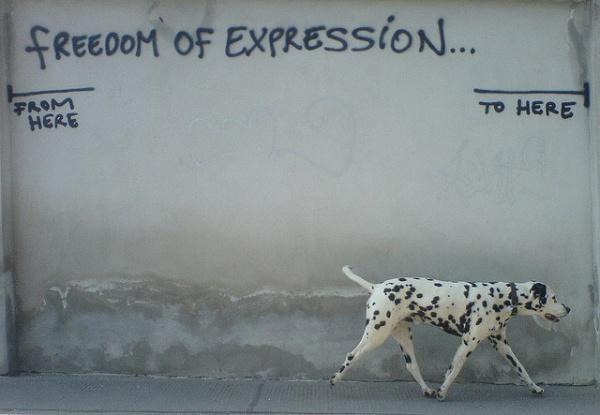

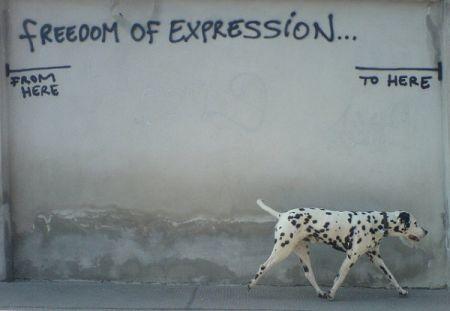

Voltaire once said ‘I may disagree with what you say but I will defend to my death your right to say it’.[1] Yet government violation of freedom of expression has been a long-term phenomenon in Malaysia.

On 19th September 2013, human rights activist Lena Hendry was charged under the Film Censorship Act 2002. Her crime? Merely organising a private screening by Pusat Komas of ‘No Fire Zone, the Killing Fields of Sri Lanka’. The award-winning documentary directed by Callum Macrae and nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, records Sri Lankan war crimes during the civil war in 2009.[2] Hendry now faces charges under section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002 for failing to obtain prior approval by the Censorship Board before the screening. The sentence is a possible fine ranging from RM 5,000-30,000, and/or imprisonment for up to three years.

A worrying feature of the on-going prosecution is the fact that the Film Censorship Act 2002 is so broad in its coverage – section 6(1)(b) forbids the ‘circulation, distribution, display, production, sale or hire of any non-approved film and section 6(1)(a) extends the law to prohibit even the possession of such material. Since the interpretation of ‘film’ includes any ‘sequence as a moving picture, whether or not accompanied by sound’, it has been suggested that even home videos potentially come under such a wide description.[3] In addition, in today’s technological era, with the prevalence of smartphones to capture any video footage, which can be shared instantly online, current provisions seem unenforceable, with total compliance neither expected nor policed.

The vagueness in the 2002 Act is also open to abuse, namely, selective and arbitrary action to any activity threatening the government’s position.[4] Tan Jo Hann, director of Pusat Komas, recently condemned authorities for allowing ‘a racist film’ like ‘Tanda Putera’ to be screened in cinemas, yet charged Hendry in her attempts to disseminate knowledge of human rights issues in a private, educational setting.[5] Furthermore, Pusat Komas has screened similar films for 11 years without prior prosecution[6] and the same film was shown to members of Parliament without consequence.[7]

In addition to the possible breach of international and UN standards, another concerning aspect of the Hendry case is the widespread apathy in recognising this as an infringement of the fundamental right to freedom of expression. The Malaysian Federal Constitution is supreme law. Freedom of expression is protected under Article 10, although subject to restrictions under Article 10(2) to preserve national security, friendly relations with other countries, public order and morality.[8] Government power to impose limitations is theoretically monitored by the courts, which can declare laws unconstitutional or question a decision through judicial review if it is illegal, irrational, disproportionate, or not been implemented using the correct legal procedure.[9] Unfortunately, the practical reality is that in controversies involving the state, the judiciary has often fail to provide the necessary check and balance, with the result similar to the concept of parliamentary supremacy.[10]

With regard to the latest developments on the case, on 10th March 2015, the High Court Judge disagreed with the April 2014 Magistrate’s Court decision that the charges against Hendry did not contradict Article 10(2), and made a reference to the Federal Court to determine the constitutionality of the Film Censorship Act 2002.[11] Counsel for Lena Hendry identified reasons for the unconstitutionality of section 6(1)(b) by arguing that the strict liability offence amounts to a total prohibition on freedom of speech and expression, renders free speech and expression illusory and ineffective, and the criminal sanctions imposed are in violation of Articles 10 and 8 of the Federal Constitution, following the case of Nik Nazmi bin Nik Ahmad v Public Prosecutor [2014].[12]

International standards also suggest that any restriction on fundamental rights must be reasonably necessary and proportionate to the objective it intends to achieve.[13] An arbitrarily applied blanket censorship of all films seems disproportionate to any aim of protecting public morality, order, security and international relations. In this case, the film was educational. It does not incite violence, and the occurrence of the Sri Lankan events had already been internationally established. In addition, any effort to ‘protect the public’ by censoring the film has been fruitless since Callum Macrae announced in February 2014 that the documentary would be accessible online for free in Malaysia.[14]

The country has faced international criticism over the Hendry case and Macrae himself stated he was shocked at what he described as an attempt to silence “such important evidence of war crimes”.[15] When the truth is substituted by silence, at what point does silence itself become a lie? The current inclination towards increased censorship is highlighted in the 2013 Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, in which Malaysia fell to its lowest ever position, dropping 23 places to rank 145 out of 179.[16] Should the government continue to impose such broad and arbitrary restrictions on freedom of expression, then this trend is in danger of becoming a more widespread reflection of the country’s human rights rhetoric. Currently, Hendry’s lawyer Joshua Tay is waiting for the Federal Court hearing on 14th September 2015. But as the case continues, it is becoming increasingly unclear whether it is Lena Hendry on trial – or the Malaysian government itself.

Interested in our strategic litigation cases? Check out the first ever Strategic Litigation Conference in Malaysia that offers the opportunity to network, share experiences and develop ideas related to strategic litigation in Malaysia – www.facebook.com/mcchr.slc

[1] Evelyn Beatrice Hall, The Friends of Voltaire (New York: Putnam’s, 1907).

[2] ‘No Fire Zone’ documentary to air online for free in Malaysia, India’, Malaymail Online, Saturday 22 Februrary, 2014.

[3] Film Censorship Act 2002, Act 620, Part I, Section 3.

[4] Ding Jo-Ann, 10 February 2015, ‘The Injustice of Lena Hendry’s Case’, Kakiseni Blog.

http://blog.kakiseni.com/2015/02/the-injustice-of-lena-hendrys-case/

[5] Chen Shaua Fui, ‘Malaysian Human Rights Activist Lena Hendry Charged in Court for Screening “No Fire Zone” Documentary on Sri Lankan War Without Censorship Board Approval’, DBSJeyaraj, 19 September 2013.

[6] Mariam Mokhtar ‘No Fire Zone: Lena, villain or victim?’, Free Malaysia Today, 4 July 2014.

http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/highlight/2014/07/04/no-fire-zone-lena-villain-or-victim/

[7] Qishin Tariq, ‘Case management for woman accused of screening unapproved documentary’, The Star Online, October 21 2013.

https://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2013/10/21/nov-7-trial-illegal-docu-case/

[8] Federal Constitution of Malaysia, Part I Article 4, 31 August 1957.

Federal Constitution of Malaysia, Part II, Article 10, 31 August 1957.

[9] LoyarBurok, ‘How free are we to express ourselves under the Federal Constitution?’, fz.com, 27 September 2013.

http://www.fz.com/content/loyarburok-how-free-are-we-express-ourselves-under-federal-constitution

[10] Tommy Thomas, ‘Malaysiaku50: The Courts’ Interpretation Of Our Constitution’ (presentation at MCCHR’s forum ’50 Years of Democracy: Has it Weakened or Strengthened Our Democracy?’, Malaysiaku 50 celebrations at Cava Restaturant, Jalan Bangkung, 17 September 2013).

https://www.loyarburok.com/2013/09/17/malaysiaku50-courts-constitution/

[11] 2015 Civil Society Voices, ‘Suspension of activist Lena Hendry’s trial’, Aliran, 25 April 2015.

[12] Lena Rasathi Hendry v Pendakwa Raya, High Court of Malaya, Application of Criminal No. 44-130 – 11/2013; see also

Nik Nazmi bin Nik Ahmad v Public Prosecutor [2014] 4 MLJ 157.

[13] Ding Jo-Ann, ‘The Injustice of Lena Hendry’s Case’.

[14] ‘No Fire Zone’ documentary to air online for free in Malaysia, India’, Malaymail Online.

[15] Callum Macrae, Statement issued in Malaysia after arrest of organisers of screening, Kuala Lumpur, Tamilnet, 4 July 2013.

http://www.tamilnet.com/img/publish/2013/07/MacraeStatementMalaysia.pdf

[16] ‘Drop the charges against Malaysian Human Rights Defender Lena Hendry’, (Statement by 112 civil society groups, trade unions and organizations, 2 October, 2013), In Defence of Lena Hendry Blog, Friday 4 October 2013.

Nice Post SEO

Nice Post SEO

Nice Post SEO