Who does the Federal Constitution belong to?

If I could cite one reason on why I love Constitutional and Administrative Law, it would be because out of all the modules, it is the one I see come to life the most, particularly in Malaysia. Recently, the one topic that has caught my — and everybody else’s — attention is the issue of hudud in Malaysia.

Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) is currently pushing for hudud to be implemented in Kelantan and this has caused tension between its coalition partners — particularly, the Democratic Action Party (DAP) who continuously insists that hudud was not part of the coalition’s plan.

In the legal sphere, many prominent lawyers have come out to state that such law would be unconstitutional. As a young law student, I seek to make sense out of this entire issue.

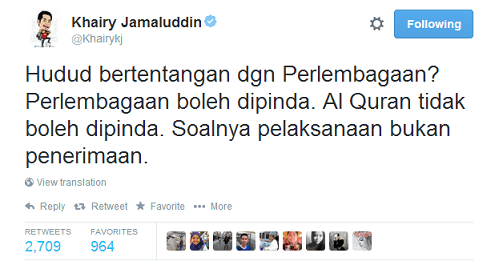

One of the arguments advanced for the possibility of its implementation was posted on Rembau Member of Parliament’s (MP), Khairy Jamaluddin, Twitter account on 25 April.

“Hudud bertentangan dgn Perlembagaan? Perlembagaan boleh dipinda. Al Quran tidak boleh dipinda. Soalnya pelaksanaan bukan penerimaan.”

(Hudud goes against the constitution? The constitution can be altered. The Koran cannot. The issue at hand is its implementation not its acceptance.)

His statement is a reminder that our constitution is a codified one; quite unlike the United Kingdom’s (UK), founded on a set of unwritten principles.

One of the weaknesses of having a codified constitution in Malaysia is that as long there is a two-thirds majority in Parliament, articles within the Federal Constitution can be altered or repealed. A good example of this would be what Dr. Mahathir (Dr. M) instigated many years ago in the process of crippling our judiciary. Article 121(1) of the Federal Constitution was amended. Initially, judicial power was to be vested in the High Court; the courts’ power was to be derived from our Federal Constitution. After its amendment, the courts are to draw their power from Federal Law. Judges’ powers are now restricted to what Parliament says they have.

What Dr. M did inherently stripped our once respected judiciary of its independence to what it is today. Morally speaking, one would of course call what he did wrong. However, he had the required support so legally what he did was not unlawful. Following this logic, as long as there is a two-thirds majority in Parliament for the Constitution to be amended to make way for hudud, we may find in the near future, the implementation of hudud will not be unlawful. In this sense, hudud can be made constitutional.

However, it is at this stage we have to ask ourselves a very important question: Who does the Constitution belong to — politicians or the regular man? To answer this, it would be appropriate to review what other acts Dr. M committed in 1988.

Apart from amending our Federal Constitution, Dr. M suspended the entire Supreme Court through the King. Our Constitution allows for a judge to be dismissed by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister. The problem with what Dr. M did was that while he was allowed to dismiss a Supreme Court judge, he was not allowed to dismiss the entire Supreme Court at once. To do that would be unconstitutional. However, as observed by the late Datuk George Seah (one of the sacked judges), nobody seemed to have made as much noise as they should have about this constitutional crisis. It was most likely that everybody was scared out of their wits of him — Ops Lalang was conducted just a year earlier. The only people who would have spoken up were in Kamunting. However, the fact that hardly anybody said anything about this entire fiasco implies consent. Would things have been different today if the older generation had decided to abandon their fear and actually speak up against this raping of our judiciary?

Commenting on the issue of Parliamentary sovereignty in the UK, Lord Hoffmann stated that “Parliament can, if it chooses, legislate contrary to fundamental principles of human rights. The Human Rights Act 1998 will not detract from this power. The constraints upon its exercise by Parliament are ultimately political, not legal. But the principle of legality means that Parliament must squarely confront what it is doing and accept the political cost.” One of the reasons why the UK has managed to survive all these years with Parliamentary sovereignty is because of the willingness of its people to be politically active.

In 2012, a minister was alleged to have called a police officer a degrading name and though he consistently denied it, he had to resign after public outcry (Plebgate incident). Although the allegations were later proved to be false, what his resignation highlights is the power of the people to demand what they want out of their MPs and Ministers. By actively bringing politicians into account in the public, violating constitutional principles, though possible, is very highly unlikely to be done by MPs in the UK.

Compare such a situation with the 1988 incidents and how Malaysians responded to it. The way Malaysians respond to horrifying acts and/or statements by our MPs and Ministers has not changed much from 1988. When some Minister says it is okay for police to shoot to kill whenever they please, we go through a short burst of public outcry and within a week or two, we just go back to our normal lives, dismissing it as “another ordinary day in Malaysia”. As for racist comments? We have conditioned ourselves to accept them as normal. We even vote for people like these.

The Federal Constitution, together with its principles, belong to us but by doing this what we have essentially done is let go of our hold of it and given it over to the politicians to desecrate. We are supposed to determine what rules and principles go in, what stays and what goes out; just like the people of the UK.

Yes, MPs have the power to alter the Constitution as long as they have the necessary support in Parliament, but if we make our wants and needs loud enough to be heard, the chances of them doing something against our wishes are highly unlikely. Maybe, just maybe, the judiciary would be better off if everybody in 1988 had collectively and actively opposed what Dr. M did rather than give him implied consent.

The time to speak up has arrived again, this time in a different form — the position of hudud in Malaysia. If anything good comes out of this, it is that we finally decide who the Federal Constitution belongs to, who shapes its principles.

Does it belong to our politicians or us?

well written.

Nice!