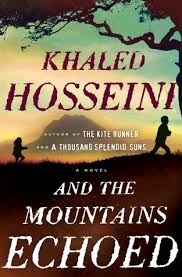

Daniel Teoh reviews Khaled Hosseini’s latest offering.

The first thing to say about this book: it is too expensive for most, too thick for many.

Most of the characters contained herein are the quiet and sensitive type, more commonly known as wallflowers. They feel people around them, and have a way to making themselves felt as well. While very much in touch with themselves, this results in most of the book focusing a tad bit too much on the intricacies of the emotional flow.

This much is very clear in two Afghan-Americans: Idris, who is the wallflower, and Timur, who struts around loud and proud, a symbol of an Americanised attitude. Idris is privately embarrassed by Timur, and seems to feel a lot seeing the state of condition his original country is in. He connected with a girl in an Afghan hospital run by foreign aid workers, and was deeply determined to help her when he returned to the US. Irony strikes when, however, he eventually forgets the hardships he saw as he delves into the comfort and familiarity of routine back home, and years later, discovered that the loud and proud Timur was the one who helped financed the girl’s surgery, assisting her into becoming a successful writer.

Reading this part reminded me of the emotionally charged “Ubah” euphoria, initial and vanishing, which swept the nation clamouring for change. Underlying this irony seems to be the author hinting at how foreign powers have helped his fellow Afghans more than local Afghans themselves.

Another thing about And The Mountains Echoed: it is narratively complex and involved more characters than the previous Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns. This has the effect of the story unfolding extremely slowly, albeit providing the reader with various points of perspective, and aids in the better understanding of how our decisions could affect people around us.

The complexity also ostensibly turns the book into a collection of short stories, a format Malaysians cannot be more familiar with.

As with previous works, Khaled personifies the tussle between Western secularism and Islamic values in Afghanistan — the infatuation of a wealthy businessman toward his driver, and the spirited Nila Wahdati who is everything “Afghan women” should not be. In Malaysia this should be something reasonably familiar as well, where many norms and taboos are somewhat institutionalised.

One interesting part is when an Afghan-American character mentioned that she enjoyed the Quran lessons her father forced her to attend when the teacher is telling stories of the Prophet’s life because she felt positively inspired, but the warm bubble burst when the mullah began to read from a long list of dos and don’ts.

Moral compromise is a recurring theme in this work, resulting in everybody in it finding themselves “corrupted” at some point. There is no Hassan ala Kite Runner, who is good and blameless to a fault. Khaled’s latest book appears to preach that fallibility is synonymous with humanity. This sets the stage for many redeeming acts and gestures of atonement, and herein lies the benefit of having multiple personas connected by the same story — readers are taken through the resonance of the impact of a decision made, whether by someone in the family or a young Greek surgeon continents and oceans away.

This book is for avid readers with wallflower personalities and tendencies, but its lessons and the emotions invoked should appeal to all, for better and worse.

The actual conditions paraphrasing and also outlining typically mistake learners of Language. This may not be astonishing since the a couple indicate much the same issues using simply a minor big difference. To start, what exactly are paraphrasing and also outlining.