Lee Kok Hoong measures the width and length of a name in Malaysia.

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

– Shakespeare

When my friend asked me to write for LoyarBurok, I expressed reservations. They want to know my full name, I said. My real name. Bonnie was quick to impress upon me that there is no reason for me to hide behind a pseudonym unless I am planning on promoting some falsehood in my writings. No, I am not. Unemployed, I am also not governed by any employment terms and conditions barring me from writing for LoyarBurok. Then, just use your real name, Bonnie said.

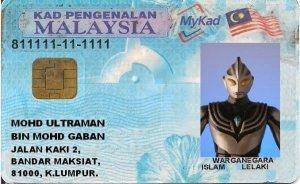

There is really nothing embarrassing about my name on my NRIC, although the pronunciation of my middle name may clearly identify my gender to all and sundry. Bonnie said that is a positive sign – historically many female authors used male names in order to increase sales or to conform to social norms. Since I am writing neither to build up a readership nor to create a following, there is no need to mask the fact that I am a Romeo rather than a Juliet. Nor is it necessary to adopt some androgynous name like Robin, Sunny, Chris, etc. I argued that writers do use pseudonyms, and some do so just to keep a low profile.

Back in the 1980s, a friend of mine found a new faith and adopted a new name which she enthusiastically used as her new byline in her news articles. Love makes us do crazy things sometimes, including changing our name. When her love story tapered off prematurely, she called me every other week about how to win back his heart. My advice to her was let it go if she had to. I also wickedly told her that with her new religion and name, she could soon be someone else’s second, third or fourth wife, legally. So, relax! A few months later, she moved to an English daily, and started writing under her birth name again. Her calls resumed, asking me for advice about executing a deed poll to renounce her religion. I was by no means a lawyer, nor pursuing my LLB or some Syariah law qualifications, and was certainly in no position to advise her on such matters. I pacified her to let the matter rest since she had not changed the name in her NRIC to reflect her faith. That was way before MyKad started including religion on its microchip.

So, what’s in a name really? Sadly, in Malaysia, more often than not, our names help others to identify our ethnicity right away. And sometimes, our religious beliefs, too. All this does not augur well for national unity, does it? While we can ignore the race or ethnic column or box on an application form, our names often betray us.

Some of us thought that all the racial undertones as well as blunt rhetoric in the run up to the GE13 would die after polling day, but the subsequent party elections gave rise to a new wave of it. In moving towards forging national unity, it is times like this that I wish I have a truly Malaysianised name which identifies me as being Malaysian above everything else, not my ethnicity. I do get envious of Swedish singer Jennifer Brown, who very well by name alone could be white or black, or even brown.

It appears fashionable for many of us to adopt an English name, sometimes motivating us to drop part of our birth name and retain only our surnames to go with it. Even “Abu Bakar” can become “Bern”. And the Peters, Pauls and Marys are just so commonplace. I remember associating with three different college mates named “Eddy Lee” at a particular point in my life, that a name like John Doe would instead have been unique.

In my working life, I adopted a Spanish name to go with just my surname on my business cards. It was a name playfully given to me by a Filipina pen-pal years earlier when I was in secondary school. I thought it was unique, unlike Peter, Paul or John Doe. But with “Rizal Lee” for a business name, I shuddered whenever I read news about religious authorities and bereaved families fighting over dead bodies. I had wondered if a similar fate would befall me if I died before I could explain the origin of my adopted name. Not that I mind getting a free burial; after all, when we are dead, we simply are. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, as they say. I can’t get a state funeral, so perhaps a burial paid by the state will suffice. But we care enough about our families when we live, and we should care enough to consider minimising their grief and confusion when we die. So I decided to drop the usage of my business name altogether, now that I am unemployed and edging closer to my grave.

Working in Indonesia years ago, I could not tell the ethnicity of their people by their names, unless they had a name like Liem Swie King. I was so impressed by such homogeneity. Their names all sounded very Indonesian to me. My local colleagues, however, told me that it is sometimes possible to tell apart a Batak from a Javanese just by their names. But it is not always easy to differentiate an Indonesian Christian from a Muslim one; for example, Yusof Wahyudono could very well be either. As for the Chinese Indonesians, many of them do retain their Chinese surnames like Tan, Lim and Wong, blatantly embedded in their Indonesian-sounding surnames like Sutandi, Halim, Wuwongso, etc.

In Thailand, the 1913 Surname Act requires everyone to adopt Thai surnames in order to enjoy Thai citizenship. That act was passed exactly a century ago! Unfortunately, I do not have Thai friends close enough to help me learn more about this subject. What I do know is that without a “korn” or “porn”-sounding name, the late Chin Peng could not have died as a Thai citizen. In all events, he was probably a Malaysian at death.

Will the Parliament someday pass a Malaysianised Name Act? With politicians adopting a divide and rule approach, I do not foresee such a day dawning in my lifetime. Hypothetically, would I give up my Chinese name and adopt a Malaysian one? Yes, I would. Before some radical Chinese politician starts suggesting that my parents would turn in their graves for the stance I take, I should warn you that I am not really a “Lee” to start with. My late father came from China at the age of nine. After the Japanese left us, he conveniently went to declare himself as being Seremban-born and that he had lost all identification papers during the war. Uneducated as he was, his surname was written as “Lee” on his new identification papers, while his brother’s was registered as “Loi”, and his sister’s as “Loo”. The correct surname for all of them, and for me and my siblings, should have been “Looi” or “Lui”. So what’s the big deal with my name or surname?

If Malaysianised names do someday come into practice, you may call me Iskandar posthumously, assuming that has evolved into being a Malaysian name by then instead of being just a Malay name. As for now, especially on LoyarBurok, my original name above would do just fine.

There you go, Bonnie. It’s really not a big deal.

Abu Bakar called themselves Burn not Bern because the word 'bakar' is a direct malay translation of English word 'burn'. Any malay with a minimal grasp of English would have detected it because of the obviousness.

If I had known Esperanto earlier, I would use Esperanto words as Akvveno. You can guest it as you know hispana.

Nice!

Loving this piece! Sometimes I feel like changing my race (no, I know I can't change my race though it can be safely said that its only possible in Msia) so that I don't have to succumb to my ancient or traditional traditons that has been passed down to me by my grandparents. Having people to look at you because of your heritage just makes me cringe, really. Worse is when they expect you to be great in accordance with your race. If you're a Malay, you must be malas. If chinese, it means you're rich. If indian, means you're a criminal. Darn it, how are we supposed to live our own lives if we continue to have these kind of stereotypes?

Thank you. I share your sentiments about the stereotyping. It is sad, but it happens.

I would just like to say that i am not sure what the rest of the Muslims in Malaysia think nor am i speaking on behalf of them. I prefer to be known and identified firstly as a Muslim then a Malaysian. it is very important to be identified as a Muslim especially to my other Muslim brothers and sisters. Having a Muslim name or a name that other Muslims can relate too will wash away unnecessary doubts on whether i am a Muslim. I have nothing against other races, I too, find it ridiculous too discriminate a person by their colour. And being a Muslim, I actually find it a beauty and fascinating especially when so much races become one with their religion, their identity, their names.

It's good you found a "sense of oneness" with those of a certain religion, identity, and even names. Just like followers of some other religions who bond meaningfully with others sharing their same faith but living beyond national boundaries.

On the subject of names, it is not always easy to identify someone by religion once we are outside Malaysia. Fair enough, Muhammad is the prophet's name. Abdullah, though a common name among Muslims, is also common among Arabic-speaking Jews, especially Iraqi Jews. Similarly, Yusof, Ibrahim, Yaacob, etc are Arabic names used by Muslims and Christians in the Arab world. They are the equivalent to the Josephs, Abrahams and Jacobs in the English-speaking world.

Even biblical names like Paul, John, Luke, etc are used so commonly today regardless of religion that they no longer help us identify the name holder as being Christian or otherwise.

Syok sendiri punya writer. No wonder u are unemployed.

Malaysianised Name? Baru turun bukit ka?. Malays already adopted arabic name, now into english name like Adam, Noah, Norman to avoid discrimination due to 9/11.

Malay name like Andika, Komeng, Jalak, Melur, Chempaka all gone.

lol shows that you don't mingle around malays that much to not even know burn = bakar. adoii.

Abu Bakar called themselves Burn not Bern because the word 'bakar' is a direct malay translation of English word 'burn'. Any malay with a minimal grasp of English would have detected it because of the obviousness.

Yes, many of us notice the obviousness. Abu Bakar is a common name of my generation. I know of an Abu Bakar schoolmate who returned from his studies abroad and started calling himself Ashburn. Yes, not just Burn but Ashburn. Very English. We told him Ashburn is more of a surname, but he said he likes it all the same, so we just have to respect that.

Then, there is Bakaruddin who actually adopted the more subtle Bernard, but we all called him Bern.