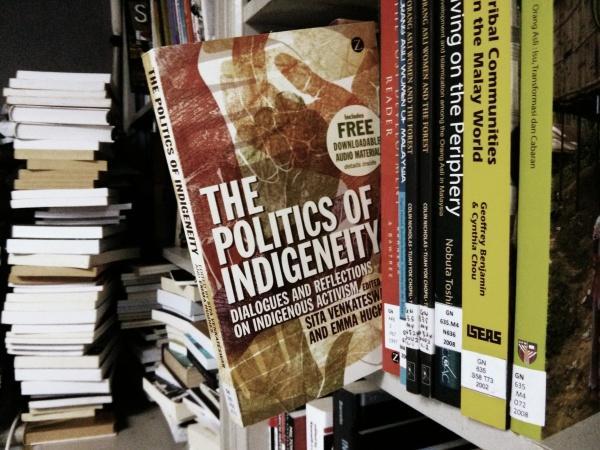

The MCCHR Resource Centre houses over 700 materials on social and political sciences. We have a growing collection of books on indigenous peoples in Malaysia and around the world. Our intern Mary O’Donovan explores the concept of indigeneity in this review of the book, The Politics of Indigeneity.

I was asked to review The Politics of Indigeneity and within moments, it became apparent that what ‘indigeneity’ means to one is almost certainly in stark contrast to another.

This book is written in three parts. In the first two, the contributors were asked to “utilize four key overarching questions/themes when conducting their discussions”. They were, “what constitutes indigeneity in the area where you work, what are the politics of indigeneity in this area, what is the vision for the future and what role do local indigenous organizations and international indigenous play in this process?”

The semantics of ‘indigeneity’ is discussed throughout the book, but one constant remains. It is a word that the colonisers, the missionaries and the oppressors, have coined to define the original people within a country. It is not a word that the original occupants willingly utilise when discussing who they are.

“In terms of the discourse on indigeneity, the Ayoreo leaders do not actually associate themselves so passionately with the term ‘indigenous’ as with their being Ayoreo. However, they also do not deny the power it holds over them; whether it is a term to be avoided in public (since it evokes negative connotations of savagery and ignorance), or to be used to gain attention in their political and social struggle.” – Benno Glauser.

“…the complex politics of naming are similar for many different indigenous groups. Having the rights kind of name is a conduit to a whole set of political possibilities within the nation-state – some positive, some less so. It is a sad reality that those struggling for rights and recognition within the state cannot simply be known by the names they call themselves but are forced to engage in a naming ‘game’ For those with the appropriate know-how this game can be played to a great effect to counter racism and institutionalized discrimination.” – Katherine McKinnon.

This provoked a thought process within. I began to question, why do we feel the need to place these people in some box? I quickly deduced that this is one way we differ to the original occupants of a land. When we meet someone we don’t know, we immediately ask, what do you do? In Australia, the Indigenous will ask, who is your mob?

We immediately define ourselves in a completely different manner. So, as I read this book, I came to realise that in our usual way of dealing with things, we had to define these groups of people in some terminology that we could understand, and in this situation, it was the term ‘indigenous’, so that we could have a point of reference to work from. It is through our own need to understand something that is different to us. They know who they are and what they want; it is the colonisers, etc. who are confused. Sadly, one obvious constant throughout the book was the hope that if the people were left with no real rights, eventually, they will be assimilated into the dominant culture. The need to rectify many years of oppression, will never have to be dealt with.

As I read, I gained a further insight into the plight of the indigenous people. In some ways, I was surprised. I was taught about my own original inhabitants within Australia via a white-dominant discourse. After many years of research and discussions, I have changed these original misconceptions (the savage standing on the foreshore with a spear watched Cook land). After reading this book, however, I felt that I have learnt something completely different. Their plight is sometimes as simple as recognition, but ironically, their recognition is via this term ‘indigenous’. A term despised by many around the world. A term which is used to oppress them, and as noted by Emma Hughes, “The Batwa have little or no time to consider the future of their people within an ‘indigenous identity’ framework because they are so consumed by immediate survival strategies.”

One theme which is prevalent throughout the book, irrespective of which part of the world they came from, is their desire to have their culture maintained and respected. For example, the Nubian people in Kenya face the dilemma of losing their identity because of their inability to educate their youngsters in their native tongue. The children are taught in schools in Arabic. As the parents want their children to succeed, they have begun to speak only in Arabic. They have realised that in order to succeed, they must assimilate within the dominant society.

When I picked up this book, I had my own personal concept on what an indigenous activist was, and I found myself realising that globally, I was in fact, very ignorant. In Australia, from a legal perspective, the focus is on land rights, sovereignty and recognition. However, the politics of indigeneity differs throughout the rest of the world.

As an Australian, I am aware of the lack of recognition given to our original inhabitants. This book discusses how Rudd apologised for the atrocities of the stolen generation and then, within months, implemented a policy that removed the basic rights of many in the Northern Territory.

In contrast to Australia, the highlanders in Thailand are still fighting just for the right to be recognised as an indigenous group of people so they can then begin the political fight for further rights. The Sudanese are fighting for their rights to be sheltered, fed and educated. For others, it is about being given the right to trade within their own country without the government removing ports and making trade an impossibility to be successful.

In the last section, the contributors were asked to address the points of connection and divergence between the perspectives presented in the discussion as well as the lessons to be learned from this context.

This section takes a lengthy approach on the semantics of indigeneity, which had already been discussed in the previous sections. Added to this, an even longer discussion on the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) and Survival International, who are all attempting to fight for the rights of the indigenous peoples. I found myself becoming cynical with their approach as they appear to be depleting the strength of one group by working through many organisations.

Their reasoning for this was explained by Simron Jit Singh, “The dialogue and reflections above offer a diversity of positions that highlight the opportunities provided to us through this project to become aware of the intersections between us rather than a single point of entry or departure.” It was at this point that I realised I was perhaps hoping to find a simple solution to a very complex question. How can we solve the dilemmas faced by so many indigenous people? Sadly, it wasn’t proffered because there isn’t a simple solution.

This book was rather interesting and as with many books dealing with the plight of the original inhabitants of this land, I find myself in quiet repose, and shall remain so until I resurface and begin to search further for some solution.

I recommend this book to anyone interested in indigenous activism as it gives insightful perspectives from across the globe.

Mary O’Donovan is a recent law graduate who actively speaks out about the plight of the Indigenous people in Australia. Upon completing her time in Malaysia, she will be interning with an Aboriginal Legal Centre in Melbourne, Australia, advocating for the rights of the Indigenous women and children.

Hi Mary

Nice to read your article. If you need more information about Australian indigenous people, you can contact the Australian Esperantist .Trevor Steele.

http://esperantowebdesign.com/trevorsteele/index….

You can find him on facebook too.