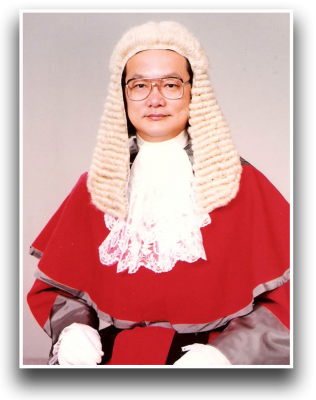

A shamelessly biased biography of the great Sarawakian, Tan Sri Datuk Amar Chong Siew Fai, former Chief Judge of Sabah & Sarawak, by his daughter and fellow member of the Bar.

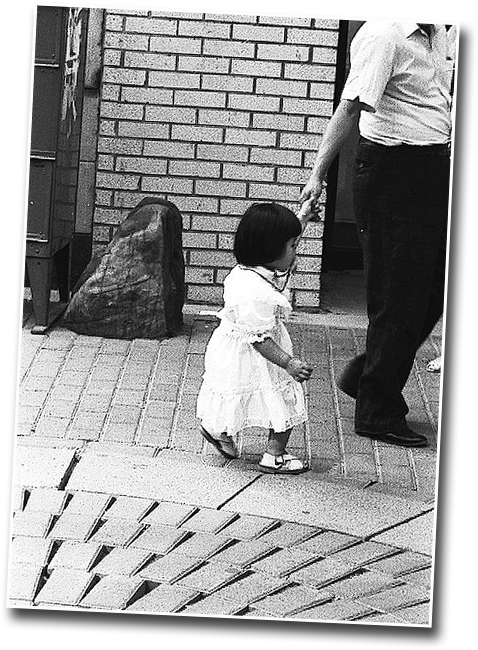

GROWING UP IN THE ’80S IN SARAWAK, I remember reading and overhearing townsfolk talk of power tussle, inequality, injustice, unfairness, political instability and of corruption in the country. I did not understand why nobody could see how simple and obvious the solution was. I had the answer to the country’s problems: vest my father with powers equivalent to that of the Prime Minister of our country. He would lead firmly, rule fairly, and in due course, all would be made right. That was the amount of faith and belief that I had in my father. I did not know then that it could never come to be because it was just not the way of the world.

GROWING UP IN THE ’80S IN SARAWAK, I remember reading and overhearing townsfolk talk of power tussle, inequality, injustice, unfairness, political instability and of corruption in the country. I did not understand why nobody could see how simple and obvious the solution was. I had the answer to the country’s problems: vest my father with powers equivalent to that of the Prime Minister of our country. He would lead firmly, rule fairly, and in due course, all would be made right. That was the amount of faith and belief that I had in my father. I did not know then that it could never come to be because it was just not the way of the world.

My father. Tan Sri Datuk Amar Chong Siew Fai (1935-2006). Chief Judge of Sabah & Sarawak between 1995 and 2000. A man I knew in two very important capacities — as his daughter and as a member of the Bar.

He was born in 1935 in Sarikei, a little town along the great Rajang River, to a couple who owned a simple Chinese medicine drugstore. He was the oldest of 7 siblings. He did what all other children did in his time — got into fights and was punished (by Grandpa), played “guli” in the back alley, swam in the river completely oblivious to the risk of drowning.

He was born in 1935 in Sarikei, a little town along the great Rajang River, to a couple who owned a simple Chinese medicine drugstore. He was the oldest of 7 siblings. He did what all other children did in his time — got into fights and was punished (by Grandpa), played “guli” in the back alley, swam in the river completely oblivious to the risk of drowning.

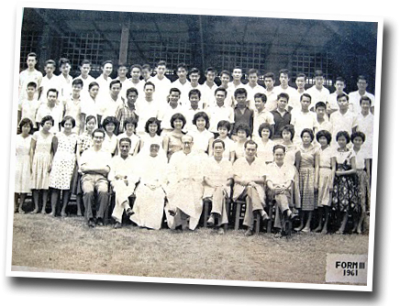

When Grandpa was ill, my father went back to Sarikei after finishing Form 3 in Kuching and took over the family business. He also took on a teaching post at St. Anthony School; he had completed only Form 3, but he studied on his own and went on to teach Form 4 and Form 5. Somewhere along the line, he decided he wanted to study law. It was a pursuit that he would have to fund himself.

For the next 11 years, he would teach in the mornings and mind the shop in the afternoons. During this time, he enrolled and self-studied through a UK study program, took the requisite examinations, finished high school, applied to and was accepted into Lincoln’s Inn. And so, armed with the money he had saved up from his years as a teacher, he boarded a ship and went to London to study law. It was August 1962. My father was 27 years old.

For the next 11 years, he would teach in the mornings and mind the shop in the afternoons. During this time, he enrolled and self-studied through a UK study program, took the requisite examinations, finished high school, applied to and was accepted into Lincoln’s Inn. And so, armed with the money he had saved up from his years as a teacher, he boarded a ship and went to London to study law. It was August 1962. My father was 27 years old.

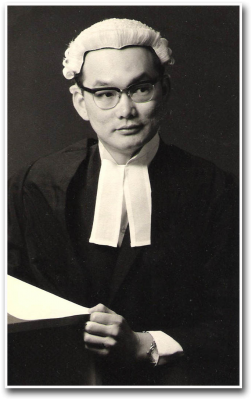

What others took 3 years to do, he completed in 18 months. Upon admission to the English Bar, he returned home to the land he loved. After three years at a firm where he learned the ropes, he started Chong Brothers Advocates in 1968. There was a new lawyer in town! He made his mark and was elected President of the Advocates’ Association of Sarawak from 1975 to 1979. Dad practiced law for 12 years. In January 1980, he was appointed a High Court Judge. He was 45 years old.

What others took 3 years to do, he completed in 18 months. Upon admission to the English Bar, he returned home to the land he loved. After three years at a firm where he learned the ropes, he started Chong Brothers Advocates in 1968. There was a new lawyer in town! He made his mark and was elected President of the Advocates’ Association of Sarawak from 1975 to 1979. Dad practiced law for 12 years. In January 1980, he was appointed a High Court Judge. He was 45 years old.

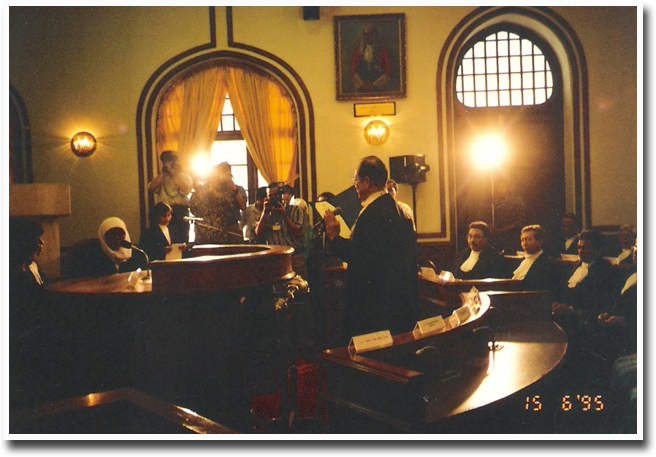

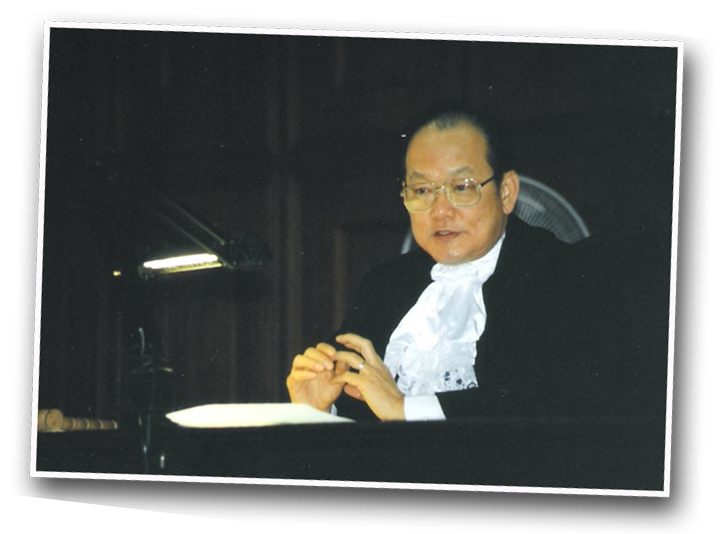

From 1980 to June 1994, he served as a High Court Judge in Kuching, Kota Kinabalu, and Sibu. In 1994, he was elevated to the Federal Court. In 1995, he was appointed the Chief Judge of Sabah & Sarawak.

Justice Must Be Seen To Be Done

I was in legal practice in the days when Dad was Chief Judge of Sabah & Sarawak and he had often sat in the Federal Court in Kuala Lumpur. I was a junior and nobody took much notice of me; so in office hallways and courtroom corridors, I often got to hear people’s honest account of him. When there were discussions of the coram that would be hearing their cases, lawyers were always happy that Tan Sri Chong was part of the quorum because at the very least, they were assured of being heard patiently (by at least one judge).

My father deeply subscribed to the aphorism “Not only must justice be done, it must be seen to be done“. Every person who walked through the doors of his courtroom would be accorded his day in court; he would have a chance to be heard fully, heard without interruption, he would have a fair hearing.

My father deeply subscribed to the aphorism “Not only must justice be done, it must be seen to be done“. Every person who walked through the doors of his courtroom would be accorded his day in court; he would have a chance to be heard fully, heard without interruption, he would have a fair hearing.

In the course of his career, he came across his share of political cases. By then, one of his brothers was deeply active in politics. Despite the close bond he had with his brother, Father was careful to always keep his distance; he refrained from engaging in any political discussion and from being linked to anything even remotely political. If he found himself in an environment where politics was in fact discussed, he would keep mum with a slight smile on his face and he would excuse himself.

Then there was the famous, or rather, infamous case of the Likas election petition. Some two years after the presiding judge had made his ruling, he revealed that he had received directive from his ‘superior’ to strike out the election petition. At the time, there were three possibilities as to who the ‘superior’ was. One of his 3 superiors was my father. That was a trying time. The media went into a frenzy. The phones would not stop ringing and reporters came to our home and literally knocked on our front doors. I asked my father why he would not make his statement. He said others could do what they deemed fit but he would stand by his brethren on the bench and he would remain silent. In any event, the truth would prevail. It always did.

Rules of the House

Growing up, although I knew I was a Christian Chinese, I was never made aware of the fact that there was a difference between myself and Hariani the girl who wore baju kurung to school or Shankini who had a red dot on her forehead. My father never referred to another according to his race or religion, and had taught me to embrace and accept the cultural and religious differences as naturally as the fact that I was so much taller than the next girl or that I could roll my tongue while she could not. I grew up in a land where it was not unusual to hear a Chinese speak a colloquial kind of Malay some Sarawakians speak, nor to hear an Iban speak fluently in Hokkien. There was no divide, we knew no racist jokes; we just existed alongside one another, as oblivious as Adam and Eve were to their nudity before they partook of the forbidden fruit.

For the most part, this remains true of Sarawak today. I do not know if this is only true of Sarawak, or that it was also true of the Malaysia back then.

As a child, my father had his share of being bullied. In his growing years, he had reacted in a way a boy would. As an adult, he dealt with things very differently. It was easy to take advantage of his even temperament and the fact that he always chose to remain silent rather than to retaliate. Remarks lined with underlying contempt and spite were hurled at him because he would not compromise on what he fervently believed was the right thing to do. He always maintained a picture of calm and serenity despite how he must have felt inside. It was difficult to witness. Often times I, clearly the more volatile of the two, seething with anger, would ask him, why did you allow that to happen? Why didn’t you say something? Why didn’t you set the record straight?

His response was always the same. Now is not the time. There is no need. Look at them. They are not in the right frame of mind to hear anything I have to say. With retaliation, an outright argument will be ensured. What good would it do anyone then? Let them say what they please. It does not matter that they think they have taken advantage of us. If that makes them feel good about themselves, so be it. As long as we are steadfast in our stance and do not waver in our conviction. All we need to know is that we did right and our conscience is clear. Better for others to take advantage of us than it is for us to take advantage of others.

His response was always the same. Now is not the time. There is no need. Look at them. They are not in the right frame of mind to hear anything I have to say. With retaliation, an outright argument will be ensured. What good would it do anyone then? Let them say what they please. It does not matter that they think they have taken advantage of us. If that makes them feel good about themselves, so be it. As long as we are steadfast in our stance and do not waver in our conviction. All we need to know is that we did right and our conscience is clear. Better for others to take advantage of us than it is for us to take advantage of others.

Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time

The Chinese have a saying: just as there are rules in one’s school, there are rules in one’s home. From a young age, my father instilled that firmly in us. We were to obey the rules within the environment we were in. Unless health posed as a threat, no concessions were made. So while the children of some family friends were able to get out of toilet-cleaning duties in the school because their powerful parents intervened, I was reprimanded for even suggesting that my father did the same for me. He would say, that is what they do in their home, not what we do in our home.

My father was a firm believer of “don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time“. If you broke a rule, you deal with the consequences.

My father was a firm believer of “don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time“. If you broke a rule, you deal with the consequences.

I remember an incident when he was a Judge. The assigned driver had parked Dad’s car illegally and a parking ticket was issued. The driver suggested that it was possible to get the ticket written off — something about it being an official car and the offence being committed in the course of conducting official duties. My father flatly refused, insisted that the consequences of a broken rule must be accepted and had the fine paid. The driver never committed another traffic offence in the 10 years while in Dad’s service. And I, knowing that Dad would not bail me out of trouble even if he could, have never gotten as much as a speeding ticket.

He exercised as hard as he worked. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays, my father played badminton while on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, he would religiously jog 12 rounds at the local running tracks the locals fondly called the “padang“. Sunday was a day of rest.

When Dad got older and badminton and running were no longer feasible, he picked up swimming and brisk walking instead. He always said swimming or running were good sports because they required patience, endurance, perseverance and sheer willpower, qualities that are important to have in one’s life and he always encouraged me to pick them up. I always rebutted saying that those sports were so boring and instead, preferred racquet sports.

Some 4 years after he passed away, I finally picked up running.

With much patience and tenacity, I overcame a knee injury and ran my first half marathon 7 months after I started running.

And I finally understood what he meant.

Often times when I run, I think of Dad in his running outfit with his hand towel hanging out of the waistband of his shorts and I wish I have had the chance to run with him and outrun him.

That would have made him smile and done him proud.

Chong Yuh Tyng is a lawyer based in Kuala Lumpur who prides herself first as a Sarawakian, and Malaysian second.

Great account!

Your dad is my example

I salute your father. I continued my study under Colombo Plan Scholarship when I was 34, married and 4 kids. I subscribe to the maxim " process of learning has the beginning but no end" Bless you for sharing.

Truly a man of integrity. Had a few opportunities to extend our services when he stayed in the hotel where I used to work. in Kota Kinabalu. Being a Sarawakian myself, it was an honor to know him and had him as our guest.

Tan Sri Chong was a great man with a kind heart. I remember an instance when I was to supposed to have a case before him and he asked the opposing counsel and me into his chamber and apologised that he had to postpone the case because he had earlier passed a death sentence on a convict. It gave me an insight into the emotions that Judges have to endure in many instances.

On another occasion after appearing before him in chamber, Tan Sri Chong invited us for breakfast with him at Lauyaken. He was a simple and humble man. Absolutely stunning character.

I used to jog with him in Sibu…

Yuh Tyng,

Indeed your father was a very respectful good judge that Sarawakians all respected. My older brothers all knew him well from Sarikei & Kuching, I personally know & dealt with your Uncle Lawyer Chong Siew Kiong in Sibu.

Obviously, your family running good blood so wish you all the best in your future undertakings & following your Dad's footsteps.

I stumbled on this site while doing research.

I had the privilege of knowing your late father who taught me this;

"Arthur,your worst enemy is your own client, therefore take all instructions for a court case in writing, for if you do not he will turn around and bite you back if you efforts do not produce the results that he thinks he is entitled to".

From the numerous professional negligence cases I handle for Insurers filed against my fellow Advocates, this have proven to be all too true.

I fully subscribe to his wise word of caution to me.

Arthur Lee

Impressive! You have a great Daddy.

Hi Tyng,

A a very touching tribute to a great Sarawakian! He was my teacher and my neighour in Sarikei, We all proud of him!

Thank you everyone for your kind words. I'd be really happy if I could be half the person Dad was.

Aunty Judy, your message means a lot. Thank you. I showed Mum too. She's very impressed that you surf the net : ))

Sean, don't call me Aunty please! Didn't know there's a family group on fb. Yes, please go right ahead. Also, please add me – it's Tyng Chong. Would love to see it.

Hello Aunty,

I hope I have your consent to post a link for this article in our family group in F/B. Your father is part of our extended Kuching family.

Absolutely beautiful article! Running is good for you!

i have a kind of warm feeling reading this :) … i heard so much abt your late father from my mom, one of his students in the class photo you have here. Hope you'll be half as good as your dad (in terms of justice), if not equally good.

Uncle Beng Sung and I always regarded your father with the greatest respect because of the qualities you so beautifully describe. I don't think this is a biased biography at all! He was a man of the utmost integrity, whom we were proud to call a friend.

"… I was never made aware of the fact that there was a difference between myself and Hariani the girl who wore baju kurung to school or Shankini who had a red dot on her forehead. My father never referred to another according to his race or religion, and had taught me to embrace and accept the cultural and religious differences as naturally as the fact that I was so much taller than the next girl or that I could roll my tongue while she could not. I grew up in a land where it was not unusual to hear a Chinese speak a colloquial kind of Malay some Sarawakians speak, nor to hear an Iban speak fluently in Hokkien. There was no divide, we knew no racist jokes; we just existed alongside one another, as oblivious as Adam and Eve were to their nudity before they partook of the forbidden fruit."

Aptly describes my observation as a Sarawakian now chambering at West Malaysia. Thanks! This is a very well-written article and it moves me in many aspects.

His written judgments speaks for him

Hi CYT,

You have a good father but more important hope you could be better especially if you happen to be in the line of justice. Bring fairness to all Malaysians and Malaysia shall be proud of you as you are proud of your father.

During my years doing my degree in law and CLP, i look up to your father very much. As he is a Sarikeian like me and was a student in our Sarikei town St. Anthony School, i was very inspired to know that one of the most respectable judges in Malaysia came from this small town. It goes to prove that no matter where you are from, as long as you have the will, you can succeed and your dad just prove that even someone from a small town can Bring JUSTICE TO THE PEOPLE.

Reminds me of my dad…he forced us for 100mtrs running with him…He will never bother to assist us when we r in trouble..he said u should be paid for our own fault..forced us to register as voter (I mean exactly when I reached 21; after birthday wish) n to vote (persistently called me during off hours, morning and night to remind me to check where’s my poll station-he said it’s your right as a citizen; rugi!),to pay my own tax, follow d rules…and proud to be a Malaysian..and love Sarawak unconditionally..

p/s: my dad, a West Malaysian Punjabi, were among d soldiers fought against communist back in early 1980's in Sarawak…married a local native (my mom)…had been transferred to Semananjung then came back here for good…He said he hates traffic jams and hectic life… he stills love bangra songs and he enjoys “bergendang” (a local entertainment popular among Sarawakian Malay and Kadayan)..

SUPPRESSING INDEPENDENCE FIGHTERS IS NOT A GLORY TO MENTION.

I’ve always put my father on a pedestal but recognized that I’m highly biased. At the same time, I was worried that my ineptness at writing (this is my first piece) might not do him justice.

Your comments are encouraging and comforting, to say the least. Thank you all kindly.

Bong, children emulate what they see around them and that education starts at home. I firmly believe that if we teach our children from a young age to embrace and accept differences, ingrain in them that not everything they read/hear is right, and teach them to make up their own minds, there is definitely hope still.

FAME TO NAME – 2804411

While a tiger leaves behind its skin

A great person leaves behind the name

To be well respected by all and kin

Simply due to integrity and deserving fame

(C) Samuel Goh Kim Eng http://motivationinmotiin.blogspot.com

Thur. 28th Apr. 2011.

Tyng,

A beautiful tribute which brought tears to my eyes. It gives us an insight into the man who was your father, a person who held steadfast to his principles and who carried out his responsibilities as judge without fear or favour. A truly courageous man. For those of us in the legal profession, this piece is significant as not only is it inspirational but it also reminds us about our bigger role as lawyers in society. Although it has been many years since his passing, his influence continues on, through you. Well done Tyng, he would have been equally proud of you.

This was a touching piece, thank you for letting us peer through the window of your life to witness such a man.

It's always refreshing to hear stories of judges such as your father, in these trying times when the public has little faith in the judiciary. It gives us hope that there are many more like him, and we do not see them only because they are just refusing to step into the limelight.

Very well expressed! Now I see why u r so much into the marathon thingy! ;)

Tyng: simple and touching. Though I was not senior enough to appear b4 him, I was fortunate to meet him in person through you. Only few judges will always be fondly remembered for their time on the bench, and undoubtedly your dad is one of them, as a judge and a great man!

Well written article. Like you too, I pride myself as a Sarawakian first, and Malaysian second. I've always wondered whether the part where we existed along the each other despite our different ethnics still hold today, what's more with more and more influence from outside the state. It hurts to think that politics has tainted much of our innocence…

He is a great man indeed. A self made man! A man of power tempered with grace. A gentle giant. I'm proud we had Borneons like him :D

As I am proud to be Penangite first and Malaysian second!

Thank you all for your kind comments. I'm proud I call him Father.

Your dad is indeed an outstanding Chinese Malaysian !

How many of the present members of the judiciary are appointed there because of his conviction and dedication.

This is not to mention most of them, if not all of them, are there because of their connection and the colour of their skin.

Great write-up. I have profound respect to what your dad stands for, even in the little things like the illegal parking 'during official duties' story.

As I am proud to be a Malaccan first and Malaysian second

CONGRATS MS. CHONG.

WHO WANTS TO BE A MALAYSIAN ANYWAY WHEN ITS MEANS ONLY THAT YOUR COUNTRY SARAWAK IS STILL A COLONY RULED BY BROWN SKIN MALAYAN OLONIAL MASTER ?

Your dad should have been made a guru to the Monkey judges in our Kangaroo Courts!…leading by example.