An expanded version of article which appeared in The Star on 11 April 2011 with a few solid tips on grammar and writing.

It seems like a huge task to restore Malaysians’ standard of English but it can be done if we put our hearts to it.

In November 1996, a Saudi Arabian Airlines 747 jet collided with an Air Kazakhstan cargo plane near New Delhi, killing 349 crew and passengers.

Investigations later revealed that the accident was partly caused by the Kazakh pilots’ insufficient fluency in English in understanding the instructions given by air traffic controllers. Needless to say, this was only one of the several plane accidents which had been caused by the pilots’ poor command of English.

Today, the rules of the International Civil Aviation Organisation require all pilots to be fluent in English. So just imagine what will happen if our Malaysian air traffic controllers and pilots are not sufficiently proficient in English. This will no doubt bring dire consequences.

English is not just the lingua franca of civil aviation, but of the world. In this Internet age, it is also the lingua franca of the Web if we want to stay connected with the world, and avail ourselves to the colossal amounts of online information.

In the 1960s and 1970s, we Malaysians were credited for having a supreme command of the English language in the region. Then, we had no lack of personalities like R. Ramani, a former Permanent Representative of Malaysia to the United Nations and president of the Malaysian Bar.

His impeccable command of English, both written and spoken, often impressed the world body and made our nation shine on the international stage.

Alas today, you and I know the sad state of English among Malaysians. I pray that we will not reach a time when all our air traffic controllers and pilots have to be expatriates because of our horrendous standard of English.

As for me, learning and improving ones command of English is also very much a personal effort.

The government and teachers can only help to a certain extent. A lot of it still depends on one’s determination to learn and improve by constantly speaking and writing the language. I attended an English primary school in Yong Peng. In the 1970s, it was still a rural village.

During my time, all subjects were already taught in Bahasa Malaysia except for Mathematics and Science before a total switch to Bahasa Malaysia in the 1970s. The switch then only involved the national schools and not the vernacular schools.

Entering Form Four, if one chose to study in the Science stream, it was as good as studying in an English school because General Mathematics, Additional Mathematics, General Science, Pure Science, Chemistry, Physics and Biology were taught in English.

For those who chose the Arts stream, subjects like History and Geography were taught in Bahasa Malaysia. In the 1970s, Yong Peng was still a rural village. As my parents were illiterate, learning English, particularly understanding the English grammar, was a great struggle.

The problem was compounded because my classmates, particularly those from Chinese primary schools, preferred to speak Mandarin. Despite having spent one year in the Remove Class, most of them were still very weak in English.

Consequently, we would first think in Chinese before forming our sentences in English, resulting in many of us speaking and writing broken English.

This explains the origins of ‘where got?’, ‘some more who?’, ‘some more what?’, ‘you go where?’ and ‘you eat already?’ I still recall with fun, for example, some of them calling ‘godson’ as ‘dry son’ since in Chinese, a godson is called gan er zi!

Looking back, I understand now the frustration of some English teachers who, at times, had to resort to using a little bit of Hokkien or Mandarin when explaining the English grammar and vocabulary. Of course, the moment this was done in class, many faces would quickly brighten up indicating that they now understood what the teachers were talking about!

I am, therefore, not surprised if teachers in rural areas today have to resort to use, perhaps extensively, Mandarin and Bahasa Malaysia when explaining English grammar and vocabulary.

It is, therefore, fallacious for some to identify only Malay students as being weak in English. During my secondary school days, the main challenge came whenever there was an inter-school meet at district or state level. I observed many of my schoolmates would feel inferior and inadequate when mixing with students from better schools due to the poor command of English.

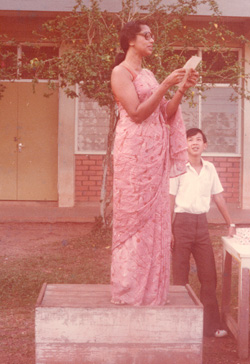

As the head prefect, the duty fell upon me whenever a school representative was asked to address the occasion. I must say there were several occasions when I was laughed at because of grammatical mistakes or pronouncing some words incorrectly. But that did not deter me from continuously wanting to better my English.

I guess being laughed at and ridiculed was the best learning method because after suffering from the embarrassment, one would not possibly repeat the mistakes.

At this juncture, I must pay tribute to three of my English teachers Yap Teong Hoon, Rose Anne Easaw and Lau Yen Fung whose passion for teaching had given hope to a rural student like me to build a strong command of English.

I still remember the day before I had to deliver my speech as the President of the Interact Club before a group of Rotarians from Batu Pahat, and Easaw, as the teacher-in-charge, spent hours helping me with the delivery, taking pains to teach me how to pronounce words like ‘sincerely’, ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘conscientiously’ correctly.

In those days, it took me at least five hours to finish an English newspaper because of my poor vocabulary. I then started having a little book, jotting down all the new words I had learnt and used it whenever an occasion arose.

I would always look at the book again, even waking up in the middle of the night if I had forgotten the meaning of a word.

Parents these days must make it a habit for their children to read English newspapers because it is indubitable that this is an indispensable tool to learn English.

Two books were of great help to me: Word Power Made Easy by Norman Lewis and Common Mistakes In English by T.J. Fitikides.

Joining the English Youth Fellowship of the St Stephen’s Church in Yong Peng as well as the singing of hymns and studying the Bible with English-speaking adults also helped immensely.

It can be quite distressing at times to notice that even some senior lawyers are not able to differentiate between simple pairs of words, such as borrow and lend, come and go, principle and principal, and dependent and dependant.

The other common mistake committed by lawyers and journalists is the word ‘counsel’ which means ‘an advocate’ or ‘advocates’ which must be used with a singular or plural verb. Hence, we do not describe two advocates as two counsels, but two counsel!

But nothing can be more stressful than to see lawyers incapable of grasping basic grammar concepts, especially with when to use the basic form of verb. Take for example, ‘eat’, ‘ate’ and ‘eaten’. ‘Eat’ is the basic verb. ‘Ate’ is past tense and ‘eaten’ is past participle.

Forget for a moment the various grammatical terms used, one must forever remember to use the basic form of verb after – to, let, can, cannot, could, could not, may, may not, might, might not, must, must not, shall, shall not, should, should not, will, will not, would, would not, does, does not, do, do not, did, did not and ought to.

As for past participle, it comes after – be, being, not being, been, not been, am, am not, is, is not, are, are not, was, was not, were, were not, has, has not, have, have not, had and had not.

Similarly, it is most disappointing to notice a sharp decline in the standard of English among our students and teachers in local universities these days, particularly law students and law lecturers. A few years back, I was shocked to discover law examination questions set by a local university containing many grammatical mistakes. Of course, if law students these days are also judged on their command of English when answering examination questions, I think many would flunk!

On this note, I have written before the importance of lawyers having a good command of English which is both in their personal interests as well as in the national interest. (see High time for a new Bar, The Sunday Star, February 6, 2011). I must add that grammatical mistakes committed in legal documents can have serious implications. Take for example, the Freedom of Information (State of Selangor) Enactment which was published in the Government Gazette on July 2, 2010.

Clause 7(1) states: “Every department shall response to the application.” The grammatical mistake is obviously the word “response” which is a noun. As explained above, one must use the basic form of verb after the modal verb “shall”. In this case, the proper word is “respond”. It follows, if the enactment had been passed by the Selangor State Assembly without any amendment, this mistake can only later be corrected by way of an amended enactment.

Finally, I have now come to the most important point, that is, it did make a huge difference to me during my time when Mathematics and Science were taught in English simply because students had more opportunities to use and exposure to the language. I, therefore, support the call that these two subjects should continue to be taught in English, at least in selected schools.

It is pivotal that our education system must not be allowed to progress at the pace of the slowest learners if we want to achieve excellence. It is illogical to say that we must revert to teaching Science and Mathematics in Bahasa Malaysia in all schools because students in rural areas are not able to cope with it or compete with those in urban areas.

If we do that, we are only perpetuating mediocrity and not moving towards excellence for students to have a chance to become world-renowned doctors, scientists, engineers and lawyers. It will also be the greatest disservice to the nation to brand such students who want to learn Mathematics and Science in English as ‘elitist’!

While it appears to be a gargantuan task to restore Malaysians’ standard of English to the glorious days of the 1960s and 1970s, we must not lose hope. The elixir to the problem is simple just let our hearts and minds follow the old true saying, where there is a will, there is a way!

The writer is a senior lawyer. You can follow him on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/rogertankm or at his blog Voice of Reason.

learning a language is quite difficult as for me. Even one language is hard to learn. for english language is the vocabulary for me. I think for native english speaker also have lot of grammartical errors right? Grammar grqmmar grammar toooo fussy. Not only english laa. But other languages too! Even malay language ,, me as malaysians have lots of mistakes in grammar, but when i speak with people (malaysian too) its oKey jerr. They could understand. Even not Malaysian whom speak Malay language to us we could understand what are they talking about. They speak Broken malay. Also got lot of grammatical errors just okayy. What is the important UNDERSTAND HUHUHUH

tak payah bising ahh . Alang2 cakap bahasa Melayu saja. Cakap pasal bahasa Inggeris ni.. hmmm orang putih pun berteraBUR grammar dorang. setakat bercakap informal kenapalah kalau ada salah sikit? mahu bercakap sama family atau kawan pun bercakap dengan formal kah?? Hahaha. Whatever. Tapi perlu juga lah mau pandai tu grammar kalau MENULIS@WRITING..

Oyah pasal SPM tu macam teda makna juga tu kalau dapat A+ subjek english sbb ikut tu graf. X semestinya terer sda bi. LAST: tidak ada juga orang yang sempurna kan? No one is perfect. Kalau lah btul2 ada orang yg blh buat karangan dgn grammar dy semua btul, konfom dpt 100%. Tp cikgu saya cakapTIADA YANG BOLEH DPT BEGITU. examiner pun tdk mau kasi bgtu walaupun dia pRO Sgt la tu bahasa.

I find it sickening that esperantists' sect are trying to PR over the blood of plane crash victims. The real reason beside it were nepotism and corruption, when underqualified pilots are assigned to profitable international flights.

On topic of Esperanto: despite all resolutions UNESCO gave but to placate those madmen, their 'language' utterly failed, having not produced anything of a cultural value. Even Hebrew, which were dead as a doornail, and definitely not 'simple', is doing uncomparable better than their junk. And yet they are trying to find more gullible victims to buy their useless merchandise.

On topic of English: do you mean that Malaisia children cannot speak Bahasa Malaisia when they go to school? Or they are not taught in Bahasa Malausian there?

I have to say Malaysian English has mixed a little (relative I know huhu) with American English. I've only noticed this couple of months ago. My Malaysian friends whom I considered were good in English have inconsistent grammar. I noticed this after hearing Australian speak and making a mental note of their grammar. Only after I have googled the sentences that they used which I find confusing that I found out the differences between American English and British English are more than just vocabulary and pronunciation. Its several things like:

-Collective noun

-Irregular verb

-vocabulary

-grammar

-I read somewhere use of 'subjunctive', can't remember what that is.

-difference in transitive (I assume verb), which I only knew after typing it into wiki :P

-indefinite pronoun

I think it is time teachers and lecturers teach their students the difference between the two. I know that when I was in school, they didn't teach us about this all of this. They only touched a little bit on the vocabulary but that’s it.

I think it is important for students to know these differences especially when Malaysia 'takes in', for want of a better phrase a lot of TV programmes from the US and people tend to learn more through television. This is translated in their written and spoken English.

For those promoting English in Malaysia, don't make our brethren feel inferior for only speaking BM or only one language. That is disrespectful to them and their language. And I see the situation got worse in the past years because of the mistake being repeated again and again by certain quarters, esp those writing to MSM papers.

Many commercial Malaysian websites catered to locals (as in, irrelevant to foreigners) are only in English, without a BM option despite the fact that BM is enshrined in the Constitution as the national language. Compare this to Thai websites, they have Thai and English; Chinese websites have Chinese and English, and the list goes on. Why aren't our websites bilingual as well?!

History shows that even a supreme law cannot protect a language on its own, only the citizens can but are they doing it?

@frand your reply illustrates perfectly why English classes are still needed in local universities, 'super irritating' as they may be

@19-year-old, huhu, you use a F-word, i shall punish you with a stronger F-word to learn esperanto and become the esperanto version editor for loyarburok.com. Free learning site in multilangual http://www.lernu.net in thai http://th.lernu.net in indonesia http://id.lernu.net don't ask why no bahasa melayu because this group of people either is igorance or as you said suport neo-kolonisme,neo colonism that English is the international language however look at the Asean,non of the country listed English as national language, and in Asia,how many countries list English as national language. Of course, you won't find it in europe and latin america. How it is proclaim as international language but the bastard English can be found every where.

I love you(r comment) Keith!

———————————

For some Malaysians, their first language is English. Their father speak English to them, their mother speak English to them, people around them speak English with them….and when they talk about learning English, they like to speak as if they put in A LOT of effort to "master" the language, HAHAHA, and throw words like "mediocrity" at people who have yet to speak (or write) in good English.

I think we have a term for that in Buku teks Sejarah. It's called neo-kolonialisme. (but the textbooks authors also didn't bother to explain what the term meant, so I dunno la…whether that term correct or not…)

Fuck people who say a pass in English be made compulsory in SPM.

I'm a native English speaker with fluency in Esperanto. If you guys would prefer to speak to me in my native language, allowing me to feel superior and my less sensitive samlandanoj ridicule your bad spelling and using the wrong synonym in a specific context while subjecting yourself to linguistic imperialism and aiding the extinction of your own language, then as we say in America, all the power to you.

BTW, everyone speaks an artificial language. The so-called "natural" languages were just created on the fly without regard for usability or consistency.

@Scott, if you can get the America Esperanto Association to shut down, http://www.esperanto-usa.org/ I would believe what you said is worth considering. Besides, your words disdain the UNESCO as this organisation recognised Esperanto in 1954. Now Esperanto is the 32nd language in CEFR http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esperanto

All your doubts can be found in the Universal Esperanto Association site http://www.uea.org People have moved on to accept Esperanto for example the Facebook page does have the Esperanto version and Esperanto speakers are all over the twitter as well. Just wondering are living with the change ?

I also like to suggest to you to write to the British Esperanto Research team to stop doing the research if Esperanto place no where in life.

http://www.springboard2languages.org

Besides, I was surprised the late Prof Dr Claude Piron short film did not touch you at all. Just look at the hit counter, how many people have watched that clip.

I hoped you were not from the camp of Noam Chomsky who said Esperanto estas ne lingvo and his statement had him suffered a lot. As a linguist, I think one needs to be more neutral to know that 6000 languages in the world are now facing dominance and will be dying in less than two decades if they are not protected.

Unfortunately, you are the one who is not saving the languages but instead of promoting the imperialism language, English. I don't blame you as you are from the Imperialist country. You should deny the saying in the book of Dr Robert Phillipson.

I leave this to other experienced Esperantists to discuss with you.

Malaysia is my country. I strongly feel that Esperanto is the best choice for her people. Malaysians should not be monolingual like America or Britiain.

What is language for ? It is for communication.

Do we need to spend about 16 years learning a language or just a year ?

The propaedeutic effect of Esperanto would bring in more on language learning.

The International Cybernatics Association has listed Esperanto as one of the official languages.

Facebook has the esperanto version page for the users. Twitter has tons of esperantists. Ipernity has the esperanto page. The list will go on if I want to write here. The latest would be the International Taekwondo would adopt Esperanto as the official language.

@Siew Chin, I hoped you did not missed out the content of the forum, I repost it here http://en.lernu.net/komunikado/forumo/temo.php?t=… . The danger of air tragedy is between the staff of air controller and the pilots. Read the aritcle, watch the youtube evidences. Read carefully The Plane Language by an experienced pilot. No one has appointed the aviation to use English as the main language.

The Chinese domestic flight use Mandarin.

@ KS Ong, I wish you can learn from the loyarburokkers who are fighting for fairness and justice. They don't join them if they cannot beat them. I learn from them a lot. They do a bit but this is good enough to enlighten someone, perhaps, more people, I don't know.

My article on Esperanto certainly have attracted many new readers out of Malaysia and from non English speaking countries. If loyarburok.com could have the Esperanto version like China media, certainly, more good thoughts would be input here.

For your information, the China Esperanto Radio has broadcasted for 45 years and is expanding into TV programmes now, read and watch here http://esperanto.cri.cn

If Malaysians have the attitudes which cannot beat them and join them,Malaysia is still under the British rule. For your information, generalisation is dangerous. In China not all people are learning English like Malaysia of which the compulsory subject is English, leaving no choices for others. Why no Spanish, French, Japanese, Korea etc for Malaysian students to choose from ?

In China, the Heilonjiang province majority learn Russian, Dalian area learn Japanese. The Mongolian learn Russian and Tibetan don't learn English but Chinese.

Besides, the illiterates rate is in high percentage.

Many people think Malaysians all speak Malay in the daily life, as a Malaysian, you are, you know well how the mamak stall scene of multilinguals.

Linguistic right issue should be your next research topic if you like to participate in the language issues.

Sinjoro Eng – one question.

Can a pilot fly a plane safely just using Esperanto?

As in anything – to excel, one must practise practise practise just like the MO of Roger Tan :-)

What a fantastic progression – from taking 5 hours to read an english newspaper to contributing articles now!!! Salute!

errr…. don't correct my english here arrrr :-)))

thank you, but as one of the law student from the local university i still cannot help from thinking English classes are super irritating

I believe one way to ensure improvement in English in schools is to make the passing of English compulsory at SPM level. This is the best way to enforce the parents ensure their kids' English are of a certain standard. Since tuition classes are already a way of life, it needs just a little bit more emphasis on English.

It will take some time before our standard of English can reach a standard like before. Closing one eye to enable students to pass when they were not of the required standard would only cause embarrassment later on in life. After SPM, there is STPM, and then university exams. But if a job requires proficiency in English, the interview and further tests would show the real standard of English of the candidates.

English used in business letters used to be 'letter perfect' but the drop in standards of English of professionals, (even lawyers, as pointed by Roger Tan) seems to be accepted with resignation and condoned so long as there is effective communication. It is like a luxury which we have to forego under our present circumstances.

Those who advocate Esperanto use are well-meaning, but the problem with Esperanto is that it’s a totally artificial language that some social engineer synthesized from several bona-fide languages. And what’s wrong with that? Nothing intrinsically–except that human nature guarantees failure. Very few people around the world want to speak a made-up “language.” People simply can’t relate to it. Genuine languages evolve organically and thus have a culture behind them. Esperanto, that made-up facade, devoid of any unified, meaningful cultural context, has always failed will always fail to attract many serious speakers.

All right–instead of “educated American linguist,” how about just “native speaker and writer.” Malaysian English is what it is, and it grates. That and the racist government deter me from visiting again.

@Scott,

Your troubled displays and fixity on semantics is almost a cry for help. I think you’ve been affected by NLPs or sub aurals and need to consider what you wrote. Also your description as an ‘educated American linguist’ makes you all the weirder. Perhaps one of those linguistic bots making random comments even?

May be our DPM can teach his fellow cabinet ministers the meaning of transformation and change to begin with ?

KS Ong said : ” We have to join the crowd for our own good if we cannot beat them. ”

No we won’t join the crowd. And writing like that merely amounts to MORE NLPs. We can form our own communities rather? Who needs to join a BAD crowd? Better the few of qualty stick together and shun a bad crowd so as to lead by example.

We cannot keep pace with the information in English being generated every moment of the day in the internet. Just imagine if we were to wait for information in English to be translated into our language, we will be left far behind. We do not have a choice because at the moment, English is the preferred language used by most IT innovators in USA and other western countries. Even India, and now China, would rather learn English to keep pace, instead of being too pre-occupied with nationalistic pride in terms of language. Malaysia has learned its lesson… or maybe not, judging from comments against moves to uplift the learning of English.

A language might be easy to learn, but if it is used by only a small number of people, what good is it as a medium of communication? We have to join the crowd for our own good if we cannot beat them.

I hope Mr Tan would take a little bit of time out of his busy time table to watch the late Claude Piron short film titled The language challenge — facing up to reality.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YHALnLV9XU

I am also glad that Mr Tan did mentioned the air tragedy

“In November 1996, a Saudi Arabian Airlines 747 jet collided with an Air Kazakhstan cargo plane near New Delhi, killing 349 crew and passengers.

Investigations later revealed that the accident was partly caused by the Kazakh pilots’ insufficient fluency in English in understanding the instructions given by air traffic controllers. Needless to say, this was only one of the several plane accidents which had been caused by the pilots’ poor command of English.’

Is there a language better than English for the air traffic ?

Yes, read it here http://en.lernu.net/komunikado/forumo/temo.php?t=5932

Now it should be clear that English is not an easy language to learn. It takes 2000 hours but Esperanto only 200 hours. I also like to invite all of the readers to read Prof Grin’s report with titled ‘ A just system’. http://www.lingvo.org

The economy of language could be easily seen from the research. Malaysia is not a rich country. Many poor children still cannot afford to study to the univerisity level. Now, I also like to invite reader to read the book author by Prof Dr Robert Phillipson “English only EU’.

English has killed many talented kids in Malaysia. Now, if we do not look forward for a change to the neutral language –ESPERANTO, more talents are going to be wasted. MUET is one of the tool that the government, in fact, the education department is putting on the throat of the students. Just imagine, we still have lots of schools are out of the cities, even in the cities, parents still have to fork out huge sum of money to send their children for tuition.

China spent 14.5 billion RMB, which is about 7 billion ringgit in learning English in 2009. The cost might be higher now. I would think Malaysia would not spend less of the amount as many professional associations are still control by the British graduates. Why the graduates of China, Taiwan etc universities are not able to join the professional associations?

We know that English is one of the imperilism languages and the 214 tribal languages in Malaysia would be killed slowly by this imperialism language. Where is the mother tongue education ? Many Chinese, Indians etc traded their mother tongue education for the imperialism language since the day that the British colonised Malaya and now is called Malaysia.

Change is inevitable and I do not deny the learning of English but just wonder how fair it would be to burden the kids with a language which needs 2000 hours of learning or we should consider a neutral language which needs only 200 hours.

By the way the Esperanto university is at here http://www.ais-sanmarino.org

As an educated American linguist who once lived in Malaysia (1986-88) I’d like to add that Malaysian English is a separate dialect with gross misuse of syllable stress, lexical pronunciation, and inadequate and constant misleading and oversimplified use of vocabulary items. The use of the word “standard” is one example. Malaysians use the phrase “standard of living” to interchangeably mean both “standard” (i.e., comfort level) and “cost” of living. The two are not interchangeable, but fuzzy language leads to fuzzy thought sometimes, and often Malaysians don’t seem to know the difference between the two concepts. In fact the word “standard” is overused in Malaysia when most of the time it’s more accurate to use other words.

Malaysians should also give “shocked” a rest. A Malaysiakini headline today mentions plane-crash victims being “shocked” but unhurt. A better choice of words would be “stunned” or “shaken.” There is also more than a hint of self-righteousness every time a Malaysian talks about being shocked about this and shocked about that.

“I’ll send you to the airport lah” is another pet peeve of mine. You don’t “send” someone to the airport if you are driving the person there. The correct expression is “I’ll take you..” or “I’ll drive you…” or whatever. We “send” someone to the airport only if we are sending them off and we are staying put.