How Rumpole helped out on a legal aid case and learning things to apply to your case.

One of the first criminal cases I handled was a charge under section 379A (theft of a motor vehicle) with an alternate charge under section 411 (possession of stolen property) against a juvenile in the Juvenile Courts where a Magistrate hears and decides the case with 2 assessors (lay people). While I was doing the case, serendipity found me in the process of devouring the Rumpole series of books written by the inimitable Sir John Mortimer, who passed away on 16 January 2009. As a quick aside, I cannot recommend the Rumpole series enough to any budding lawyers, particularly those inclined towards criminal practice. According to legend, Amer Hamzah, currently one of the Bar’s most promising criminal legal practitioner, was inspired by a Rumpole collection to take up his first legal aid criminal case and led him down the criminal path. One of the Rumpole stories actually helped me to appreciate a piece of evidence that was key to my winning the case.

I forgot the name of the story but remember the instance of relevance vividly enough. In that story, Rumpole was defending one of his regular clients over an offence. What complicated his defence was a written admission his client purportedly signed admitting to the offence. The admission was given under duress. He had trouble proving this because his client lacking credibility due to their frequent visits to prison. Despite this Rumpole found the single thread that would unravel the entire prosecution’s case because of a word used in the admission statement. It was a slang word that his client would not use but one a cop would. And so his client was acquitted.

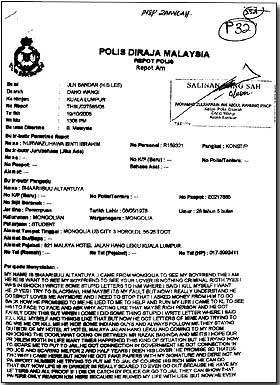

In my case, it concerned the police report lodged instead of an admission. According to the police report, while the RELA volunteers were carrying out their security rounds, they spotted my client behaving suspiciously among some motorcycles. They arrested him and when they searched him they found keys on him. They took the motorcycle, my client and his friends down to the police station.

The entire report was fiction.

According to my client, some RELA volunteers questioned him and some friends why they hung outside one of his friends’ low cost apartment one morning. He was playing with his mobile phone at the time. The RELA volunteers in their questioning of him implied he stole it. My client answered back not very politely and no doubt made some derogatory remark about them. They left for a while but came back about 30 minutes later arresting all 3 of them for purportedly stealing a motorbike.

Naturally, the prosecution had to call the person who lodged the police report, a RELA officer. Interestingly the prosecuting officer (a legally qualified police officer not a deputy public prosecutor) did not thoroughly go through the facts of the offence with him. He just asked him a few general questions and asked him to verify the police report to have it admitted. With Rumpole’s somewhat story fresh in my mind, I noticed how the witness expressed himself orally in evidence did not feel consistent with how the report was written. The words he used and the sentence structure was different even if you account for the difference between expressions done orally as compared to in writing. It just felt ‘off’.

I pulled at the thread. I did not initially refer to the police report. Instead I asked the witness to set out the facts from his memory. Before he completed his recitation of the events, he contradicted a lot of the material facts in the police report. It was so different that I had the confidence at that early stage in practice to pointedly accuse him of not writing the report. What surprised me even more was his admission of it. He named the purported author of the report.

So he was the next witness, also a RELA officer. It was clear from his demeanour on the stand that the ‘author’ did not think he would ever be called to the witness box. He was nervous and not composed. The prosecuting officer committed the same error by not taking him through the facts, merely leaving the ‘author’s’ confirmation that he wrote it. I applied the same approach as the first witness and not before long he confessed that though he wrote the report, he took instructions from another RELA officer who was the one that directed the report to be lodged in the first RELA officer’s name. By this time the Magistrate was furious and scolded the witness for lying.

This was my first ‘direct’ experience with RELA officers and have not been impressed since. In this case 3 RELA officers tried to fix a kid up for a crime simply because they felt he was being disrespectful. This simple case took almost a year and a half to complete. Throughout the trial, the RELA officers and the policemen would often approach my client and his mother and to persuade my client to plead guilty. ‘Sure lose one this case’, ‘Why you want to bother fighting? All our witnesses are RELA officers. Who would they believe?’, and so on that they would keep harassing my clients. It got to the point where I had to sit with them because at one point my client was taken in and wanted to plead guilty due to their incessant persuasions. The officers would not approach them when I was around. That was one good reason to grill those RELA officers on the stand.

With those witnesses it is no wonder we won the case. No prizes for guessing that the prosecution also lost at the prima facie stage. I informed my client’s father that he could lodge a police report for perjury against the officers. The record reflected their crime. The nice thing about that family was that despite all they had been through, they had no malice for the officers. They just wanted to get on with their lives. He said as far as he was concerned it was over and he wanted his kid back to school.

And the lesson here? You can learn from just about anything, even from books of fiction you enjoy, and most definitely from the great Rumpole! Though the story may be fiction, the lesson contained certainly isn’t.

what a way of how justice is done