How the Rule of Law is measured in a country according to the 2010 Rule of Law Index, and a brief analysis of Nazi Germany and Apartheid South Africa which exemplify a corruption of the Rule of Law – the Law of Rules.

Recently, I had the pleasure of attending the Asia-Pacific Rule of Law Conference in Kuala Lumpur, a symposium coordinated by the World Justice Project focused on, and you may have guessed it, the Rule of Law.

The WJP, a non-profit based in Washington DC started by the President of the World-Series-Champion San Francisco Giants, flew in almost 150 of the regions most renowned lawyers, business investors, CEOs, entrepreneurs, members of civil society, UN officers, environmentalists and grassroots activists to partake in a two-day, multidisciplinary examination on the Rule of Law – in both a conceptual and palpable fashion.

The conference, prompted by the WJP’s release of its 2010 Rule of Law Index, was conceptualized based on the WJP’s broad-based notion of the rule of law, which posits that the rule of law can only be effectively advanced through multidisciplinary collaboration. While governments and organizations tend to vary on the definition of the rule of law, WJP uses a working definition grounded in four universal principles:

(1) an accountable government under the law

(2) clear, publicized, stable and fair laws that protect fundamental rights

(3) fair, efficient and accessible administration and implementation of the laws

(4) access to justice provided by competent, independent and ethical adjudicators.

In what is becoming an increasingly more popular and thus no longer novel approach, WJP employed a multidisciplinary task force to address the grandiose idea of the rule of law.

The conference, however, was not quite the spectacle I envisioned. It was simply, for lack of more nuanced parlance, boring. And by the mien of other participants, who I caught dozing in and out of daydreams that surely had brought them to a more arousing place, the weariness was not endemic to me.

I was expecting a rousing collaboration between money-hungry CEOs and environmental zealots on how to reconcile economic development and environmental preservation. But instead, I was delivered perfunctory PowerPoint presentations and humdrum Q & A sessions. I was expecting fierce debate between haughty International Labor Organization (ILO) officials and fiery migrant-rights NGO activists. But instead the ILO cadre spoke about lofty and impersonal international guidelines, and the NGO group summoned poignant, yet narrowed personal narratives, neither of the two converging on a discussion that would be both exhaustive and practical. My disparaging assessment should be taken with a grain of salt, however, as I was unable to sit in on the plenary sessions where more robust conversations ostensibly took place.

This mediocre discussion notwithstanding, I was incredibly moved by the keynote speaker, Michael Kirby, a former Justice in the High Court of Australia. Mr. Kirby, also an openly gay man (and knowing a little bit about the demography of the participants, I am sure some heads were turned when he divulged that tiny secret) spoke about the history of the notion of human rights and the international guidelines that have helped shape the rule of law throughout the world. Underpinning his speech was a straightforward yet invaluable theory: it is not the law of rules that determines the legitimacy of a society; it is the rule of law.

This idea has historical foundations, as well as implications for current and future national conflicts and political systems. The logic follows that simply because a society has a clear, administered set of laws and regulations, does not necessarily mean it is a glowing example for rule of law. Let me break the distinction down to you through two events that happened in the last century – Nazi Germany and the Apartheid.

Sorry to do this, but try and transport yourself back to the time of the Third Reich and Nazi Germany. Governing this increasingly authoritarian and nefarious nation was a well documented and clear set of rules, most notoriously of which purported the Aryan claim to superiority. Supported by the rise of Hitler and his minions, the German state systematically adopted policies that subordinated other ethnicities and set the stage for WWII.

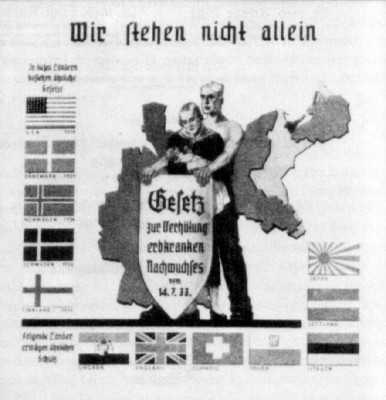

Now, following WJP’s definition of the rule of law, Nazi Germany satisfied the precept of “clear and publicized laws” and “fair, efficient and administration of the laws” with predictable outcomes. People knew what to expect. But, would anyone in his or her right mind agree that Nazi Germany exhibited even an inkling of the rule of law? No, that would be preposterous, because while it was a land governed by the law of rules, the rules themselves, like the Sterilization Law, which authorized the German government to sterilize anyone they deemed to possess a “genetic disease” (i.e. anyone outside of the Aryan race) were complete bundles of xenophobic propaganda. It was not the implementation and administration of the laws, or even their publication and clarity, that was debilitating, but rather the laws themselves.

Fast-forward and travel thousands of miles South to the tip of Africa, where the Apartheid regime of South Africa was flourishing. The country was governed on the basis of a legal, racial segregation system that severely curtailed the rights of “non-whites” to preserve the “white” minority rule. In similar fashion to Nazi Germany, this society had a clear and observed set of rules. Non-whites knew they could not eat at the same restaurants as whites, and were quite aware of the limited and derelict educational options afforded to them. Furthermore, as Justice Kirby notes, there was also relatively strong judicial independence, and the government rarely interfered with judicial processes. However, is Apartheid South Africa an environment we associate with a robust rule of law?

If you do, I don’t even think tiga suku would be the appropriate word for your dementia. Yes, judges were independent, but the law they were asked to follow was, at every level, a racial onslaught against the inalienable rights of the majority of South Africans. So even with clear laws, fair administration and implementation of laws, and independent judicial adjudicators, a society will still lack the rule of law if the laws themselves are not fair and impartial.

And I think this distinction between the law of rules and the rule of law helps to clarify the ongoing revolutionary wildfire that is spreading in North Africa and the Persian Gulf. For many years, autocrats and theocrats have governed these countries, using iron-fisted rules to clamp down on any glimmer of dissent. So, by some criteria, these nations have been organized through clear law, albeit I am sure many would argue even that standard does not hold up to the test of truth. But regardless of the administration of the law, it is the rules themselves, those blatantly censuring civil and political rights, which have been the real cause of social unrest.

So I pose to you Orang Malaysia, seeing as I am a newcomer to this country, how do you think Malaysia stacks up in this regard? How does it fare in each of the four principles WJP outlined under the rule of law? How would you compare it regionally to other Asia-Pacific countries?

From my perspective working with the Child Act and juvenile justice in Malaysia, there has to be improvements made to the laws themselves, especially an amendment supporting diversionary options and restorative justice approaches for children that come into conflict with the law. And I am sure you all will have some choice words about the rule of law in other aspects of Malaysian society. I have a tiny feeling the letters ISA might arise in this conversation…

Liam Hanlon hails from the inner city streets of San Francisco, where he served as a full-time Mexican-food aficionado, part-time social activist, and even smaller-time student. After attending UCLA for his bachelor’s degree in Political Science, Liam moved to Geneva, Switzerland for a year, working for the international legal-rights NGO International Bridges to Justice. During this stint, he co-coordinated the 2010 Asia JusticeMakers Competition, which sourced and funded local legal-rights initiatives throughout Asia. After a two month hiatus scouring the lands of Southeast Asia with his rucksack, Liam moved to KL in October 2010 to begin documenting the work of one of the JusticeMakers Fellowship receipients, Dato’ Yasmeen Shariff, for her work with juvenile justice. He has since shifted his to time to interning for another NGO Voice of Children, as well as transforming into a LoyarBurok minion.

Dear Aerie

When you compare the subjectivity of laws to morals, I suspect you mean that they are subjective to this irksome notion we call emotions, which have a tendency to change according to space and time. To a degree our understanding of morality is often confused by visceral impulses — disgust with something we don't approve, moved by something we pity, joy at the triumph of the good or the underdog. Even though our emotions have added an extra impetus for us to pursue certain moral causes, they are by no means the only way, or even the necessary way, for us to appreciate morality. Morality needs to be divorced from our emotive rationales long enough to see it for its outcomes and results. Morals and laws have to stand on clear principles which are inalienable to all human beings. They cannot afford to be subjective even if we like to appeal to their subjecitivity — especially when they are in favour of our prejudices.

That is true, laws are subjective. To some they seem legitimate, to others they seem unjust. And, as you were saying, this wholly depends on a completely subjective perspective.

Nevertheless, as a global community, we have come to understand certain rights as "inalienable," and we accept international guidelines for fair governance and practices. Indeed, some of these examples, most notably Nazi Germany, didn't necessarily sign on to any treaties precluding them from adopting their racist policies. But still, there are a myriad of examples where countries formally promote human rights and ratify international treaties, but nevertheless, maintain domestic policies that would indicate otherwise (i.e. look at Malaysia's reservations to the CRC)

I am trying to avoid an existentialist debate on what is "right" or "wrong." We can go on for ages if we follow that route. In my argument i was referring to a more pragmatic approach to rule of law, one that observes the human rights that we have all come to understand as universal.

Thoughts? Thanks for the comment

Hello Liam,

First, I agree that societies in Nazi Germany and Apartheid South Africa were terrible to allow those atrocious practices. Clearly these laws lacked humanity and were wrong.

However, the concept of laws are subjective in nature, kind of like morals. We might think Apartheid was wrong, but the Afrikaans in South Africa feverishly believed that they were correct. Same goes to the concept of Aryan supremacy in Nazi Germany.

I'm not saying that they're right. I'm just curious as to how when these laws were universally wrong in our eyes, how these people can believe it to be just and screamed of legitimacy?