Avyanthi (Avie) Azis writes on the undocumented struggling to make sense of life and love in Kuala Lumpur. This is a three-parter series, read Part 1and Part 2.

As a country in which Muslims are the majority, Malaysia’s apathy often baffles me. The situation reminds me of a satirical piece written by A.A. Navis, a master story-teller from West Sumatra. I know Hamka and Mochtar Lubis are widely read in Malaysia, I don’t really know if Navis also attracts a considerable audience.

His most famous short story is called ‘Robohnya Surau Kami.’ My generation had to read it in junior high. The Collapse of Our Prayer-house. (Notice that Navis uses the word surau. Sumatrans are more Malay than other Indonesians who refer to the prayer-house usually as musholla.)

There is a story inside the story, telling us of a hajj who appears before God on Judgement Day. The hajj is confident that he is about to enter Heaven.

But God stands on his way and asks,

“What have you done during your entire time on Earth?

The hajj said, “I worshipped You night and day, my Lord.”

“Lain?” God asks. And other than that?

“I went on a pilgrimage to Mecca, O God.”

“Lain?” God still insists. The pressure is on. The hajj breaks into cold sweats but they immediately evaporate because the gate of Hell has been opened up for him, and now the fire is glaringly impending.

“Lain?”

The hajj had not done anything else during his entire time on Earth. He let his children perish in poverty, he left his fellow countrymen to fight the Dutch by themselves during the War of Independence. He did not care about other people. He just prayed and prayed for himself. He chose the easy path, the convenient one. He didn’t shed blood, sweat or tears.

Islam, at least in the way I understand it, relies on two pillars: devotion to God and compassion toward others. The hajj, like so many of us, abandons others and seeks only to save himself. In Navis’ story, God says that He’s not crazy about praise and flattery. He simply doesn’t want us to be armchair believers.

But armchair believers, remote from active involvement, seem to be the norm.

One Rohingya man I met eloquently lamented, “The world we live in, is no longer one that is guided by the norms of religion. It does have faith, but it subscribes to a faith in technology and documents.”

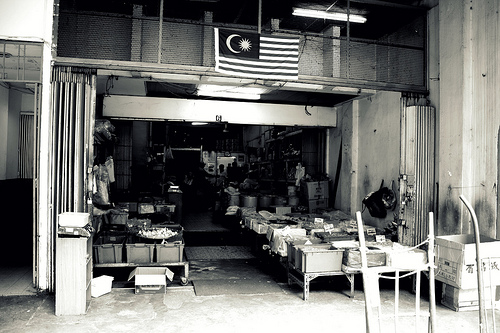

With that faith, we citizens accept appalling scenes as normal, as if they are naturally a part of daily panorama. We let Rela raids wherever they please (I remember hiding for hours on end with my ‘illegal’ respondents from them in a little Burmese shop in Kota Raya). We put people in jail just because they have no papers.

Here in Malaysia, I came to the conclusion that love exists, but is often very exclusive. No, no, no, no, no, Love with a big L is a language we no longer understand. We understand only loves that come with the little l’s. It is the love we have for our lovers, parents, children, friends, pets. Selfish loves that come so easily for us because these people are one of our own.

Amitav Ghosh once said the opposite of love is not hatred but cowardice, and so we have become, people who do ‘what is technically correct, but not what is right.’

I don’t judge Malaysia or Malaysians, but I do deeply resent this difficult world of fictional but definite boundaries.

There was a school set up for Rohingya children in Puchong. I often came just to watch the children sing as loudly and as off-key as they could. One of the songs had the following lyrics:

The place to be happy is here

And the way to be happy is to make others happy

And to make a little heaven down here

Tell me, why does Malaysia refuse to get heaven in this life and after? Discriminating children is something that I completely refuse to understand. OK lah if you don’t want to accept parents, but since when are children guilty of their parents’ migration? I came to know some of these children in Puchong well. They would sing ‘Negaraku‘ proudly, not yet aware that their Negara considered them unworthy foreigners and put ‘warga negara asing‘ on the nationality column of their birth certificates (if they gave them at all). They had no memories of Burma.

How could they be warga negara asing when they only knew Malaysia? From time to time, Shukur, my favorite among the students (he was asthmatic and often absent from class) would honor me by singing a cheesy tune from Indonesia, ‘Apa salahku.. apa salah ibuku.. ‘ Not the best example of our culture, to my regret, but they told me the song was very popular in Malaysia.

***

There was a memorable Rohingya girl in Klang, named Robizan. She had experienced a brutal police raid. Not satisfied with taking her parents, they took her to detention too. They shaved her head and she screamed like hell. When I met her, her hair had not grown back to a length proper for a girl. But she did not indulge in sad stories.

She was more interested in my own tragic situation. “Kakak dah kawin ke?”

Girls around Robizan’s age were always so disappointed when I replied negatively to the question. To appease the dismay and to render myself a less pitiable singleton, I’d entertain them with tales of an imaginary fiance back home. Sometimes he’s a veterinarian, other times he’s an IT guy, I could never set my story straight.

Those who did not call my b.s. offered to set me up with their brothers/uncles/etc. The match-making reminded me of a ‘mencari jodoh‘ advertisement pinned on a tree near the Bank Negara KTM station. One of the lines in the ad said, ‘Tak kisah apa status Anda.’ And I wondered if I would live to see a day when Malaysia decides to do away and tak kisah with one particular status they now stamped on those without papers: ‘illegal.’

***

Back in the Arrival Hall. Still plenty of time to people watch. My mother thought it a bad habit (“Why are you always eavesdropping?”). A tall, European lady in designer jeans and stilettos attracted people’s attention. She had a young daughter. They spoke in awkward English. The lady asked if the little girl could spot her daddy among the crowd, “Do you see him? Can you see Daddy?” For some people, the privileged ones, a certain airport’s arrival hall is bound to be one of the familiar sites of childhood.

I too, was one of those spoiled brats picking up daddy at the airport. Years ago, at the Soekarno-Hatta (which resembled a bus terminal more than an airport), I used to cling to the rusty arrival gate, buoyant at the sight of my father returning from work overseas. Invariably, he’d bring back new toys, stuffed animals, Lego but always, there would be chocolates in his hand. The same chocolates are still sold in the airport. The same lines of shops are still selling the same souvenirs for loved ones: perfumes, books, bags, sweets..

The Arrival Hall was packed with families anticipating loved ones. For them, separation was not something permanent. They knew when their loved ones were due to arrive: the exact date, the ETA, the specific flight number that carried them. The people they waited for, also knew the terms and conditions of their exile: it was largely self-imposed, and temporary.

One family came rushing forward. A father with two kids. When I was able to look more closely, I saw that the father was Chinese. The children however, looked Indian, darker skin and poignant nose, save for two imitated pairs of their father’s eyes. Chindians. I have always been a major fan of interracial children. They stir in me a stubborn hope that a tolerant, open-minded future is possible.

The older child was a boy. Maybe twelve or thirteen, around that age. Difficult years to be in. He wore thick glasses, looked bookish, and seemed to have that annoyingly cute habit of knowing the answers to every problem. He happily provided comments for everything and everyone.

A group of flight attendants in purplish bonnets passed us by.

“Look! They’re Russians!” the boy excitedly announced to his father.

“Ha! And how do you know they’re Russians?”

“Because they speak Russian!”

“And you speak Russian?”

He uttered some words. Russian or gibberish, I couldn’t tell. After a while, the boy grew tired of convincing his skeptical father and quieted down. At first I thought he was sulking. But he was not. He was gazing intently at his baby sister, half watching over her, half lost in thought. I wondered what went on his brainy head and apparently his own father was curious too.

“What are you doing?” The father said, breaking the silence.

Nothing could ever possibly prepare me for his answer as the Chindian boy calmly said, “Nah, I’m just waiting for the sky to fall.”

Avie Azis survives on a string of odd jobs. She is now doing research on fiddler crabs. She hates the fact that thosai and ice cream soda are very difficult to find in Indonesia.

I like people that cares and people that have compassion. Whenever we help someone and feel sad for others is feeling I hope to have all the time. We should try to help whenever we can. Not necessary religion should be in the picture when we feel for fellow humna being. We should not use religion to start any disaggrement. Religions still exist when we die as religions were here long before we are here. I want to thank you for the young people that are around to make our country a better place. And someday the young people will make the world a better place. I am in Cairo while during the Mubarak protest crisis and I can feel everyone is helping each other during this difficult time regardless of religion

Before this becomes skewered as a religious debate, siewchinteo, "it has been said"? How about investigating what you've heard said? The "Old Bible", if you're talking about the Christian holy text, is full of God's commandments about protecting the more vulnerable. Here's a small sampling for your consideration:

Exodus 23:9 "Do not oppress an alien; you yourselves know how it feels to be aliens, because you were aliens in Egypt."

Leviticus 19:13 "Do not defraud your neighbor or rob him. Do not hold back the wages of a hired man overnight."

Leviticus 19:33 "'When an alien lives with you in your land, do not mistreat him.

Leviticus 19:34 "The alien living with you must be treated as one of your native-born. Love him as yourself, for you were aliens in Egypt. I am the LORD your God."

Leviticus 25:35 "'If one of your countrymen becomes poor and is unable to support himself among you, help him as you would an alien or a temporary resident, so he can continue to live among you."

Deuteronomy 1:16 "And I charged your judges at that time: Hear the disputes between your brothers and judge fairly, whether the case is between brother Israelites or between one of them and an alien."

Deuteronomy 10:19 "And you are to love those who are aliens, for you yourselves were aliens in Egypt."

Deuteronomy 23:7 "Do not abhor an Edomite, for he is your brother. Do not abhor an Egyptian, because you lived as an alien in his country."

Deuteronomy 23:16 "Let him live among you wherever he likes and in whatever town he chooses. Do not oppress him."

Deuteronomy 27:19 "Cursed is the man who withholds justice from the alien, the fatherless or the widow." Then all the people shall say, "Amen!"

Psalm 146:9 "The LORD watches over the alien and sustains the fatherless and the widow, but he frustrates the ways of the wicked."

Jeremiah 7:6 "if you do not oppress the alien, the fatherless or the widow and do not shed innocent blood in this place…"

Jeremiah 22:3 "This is what the LORD says: Do what is just and right. Rescue from the hand of his oppressor the one who has been robbed. Do no wrong or violence to the alien, the fatherless or the widow, and do not shed innocent blood in this place."

Ezekiel 22:7 "In you they have treated father and mother with contempt; in you they have oppressed the alien and mistreated the fatherless and the widow."

Zechariah 7:10 "Do not oppress the widow or the fatherless, the alien or the poor. In your hearts do not think evil of each other."

Instead of comparing religious "yours versus mines", perhaps we should look into our own consciences and earnestly ask ourselves what is good and just and right. Then we can choose or change our culture, religion, ideologies and philosophies accordingly as our hearts lead us, or adapt to new ones accordingly, if the current ones we have been holding to go against our conscience. This is a personal journey. Let's keep the discussions helpful here – this is a limited medium and vitriolic statements become exacerbated within its constraints, taking on a disproportionately loud voice.

Can we bring the debate back to what we as human beings ought to be asking ourselves when we see people like Shukur? – what does your conscience tell you about a) how he should be treated fundamentally as a person; and b) whether he is anak bangsa Malaysia, born and bred here? Those are the real issues being thrown up for reflection in this article, I think.

Ali Davidson – it has been said if you want to see the most terrible things, massacres, go and see the Old Bible.

Avie,

I don't know where you get your understanding of Islam from but calling it 'compassion' is a bit far fetched. Unless you are joking. If you are, then I am laughing with you…. HAHAHAHAHA!

Quran (9:30): “And the Jews say: Ezra is the son of Allah; and the Christians say: The Messiah is the son of Allah; these are the words of their mouths; they imitate the saying of those who disbelieved before; may Allah destroy them; how they are turned away!”

Quran (9:38-39): “O ye who believe! what is the matter with you, that, when ye are asked to go forth in the cause of Allah, ye cling heavily to the earth? Do ye prefer the life of this world to the Hereafter? But little is the comfort of this life, as compared with the Hereafter. Unless ye go forth, He will punish you with a grievous penalty, and put others in your place.”

Bukhari (52:177): Allah’s Apostle said, “The Hour will not be established until you fight with the Jews, and the stone behind which a Jew will be hiding will say. “O Muslim! There is a Jew hiding behind me, so kill him.”

Qur’an (22:19-22): “These twain (the believers and the disbelievers) are two opponents who contend concerning their Lord. But as for those who disbelieve, garments of fire will be cut out for them; boiling fluid will be poured down on their heads. Whereby that which is in their bellies, and their skins too, will be melted; And for them are hooked rods of iron. Whenever, in their anguish, they would go forth from thence they are driven back therein and (it is said unto them): Taste the doom of burning.”

Muslim (16:4131): They were caught and brought to him (the Holy Prophet). He commanded about them, and (thus) their hands and feet were cut off and their eyes were gouged and then they were thrown in the sun, until they died.

Qur’an (33:36): “It is not fitting for a Believer, man or woman, when a matter has been decided by Allah and His Messenger to have any option about their decision.”

Bukhari (88:219): “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler.”

Qur’an (4:24): “And all married women (are forbidden unto you) save those (captives) whom your right hands possess.”

Abu Dawud (2150): “The Apostle of Allah (may peace be upon him) sent a military expedition to Awtas on the occasion of the battle of Hunain. They met their enemy and fought with them. They defeated them and took them captives. Some of the Companions of the Apostle of Allah (may peace be upon him) were reluctant to have intercourse with the female captives in the presence of their husbands who were unbelievers. So Allah, the Exalted, sent down the Qur’anic verse: (Qur’an 4:24) ‘And all married women (are forbidden) unto you save those (captives) whom your right hands possess.’”

Qur’an (8:55): “Surely the vilest of animals in Allah’s sight are those who disbelieve”

Ibn Ishaq: 327: “Allah said, ‘A prophet must slaughter before collecting captives. A slaughtered enemy is driven from the land. Muhammad, you craved the desires of this world, its goods and the ransom captives would bring. But Allah desires killing them to manifest the religion.’”

Ibn Ishaq: 992 – “Fight everyone in the way of Allah and kill those who disbelieve in Allah.”…Muhammad before a military attack.

"Compassionate to others"? Huh? What?!