On 19 June 2018, SUARAM held the launch of its annual human rights report at the Chinese Assembly Hall in Kuala Lumpur. At this event, the human rights situation in 2017 and expectations for 2018 were discussed, particularly in light of the change of government in Malaysia for the first time in 61 years that leaves much hope for more effective changes to be made for human rights in Malaysia.

Issues in relation to 11 human rights areas are discussed in the Report. The first issue addressed is detention without trial. A written reply from the final parliament session of 2017 stated that until October 2017, 1,614 individuals have been detained under various laws without formal charges under laws such as the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA), the Prevention of Crimes Act 1959 (POCA), the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2015 (POTA), and the the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (DDA). SUARAM therefore recommended for the abolishment of these laws, total cessation of the practice, the release of minors detained under these laws, and for inquiries about reported abuses.

The second area is police abuse of power. Improvements were made in 2016 regarding this matter, however they were reversed in 2017 with an increase in the number of reported cases of police brutality, torture, chain use, and deaths in police custody. Reports of torture of detainees are still common, particularly by using chains. Police shootings still occur as well as enforced disappearances. The kidnapping of NGO Harapan Komuniti founder in 2017 with the suspected involvement of state authorities is a case in point. Furthermore, recommendations by SUHAKAM and EAIC have remained unaddressed and there have been no initiatives by PDRM to implement any change.

Freedom of expression also remains an ongoing concern. Although the application of the Sedition Act has significantly reduced since its peak in 2015, it is still used on various occasions to stifle political dissent. Meanwhile, the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) has been used to investigate 269 cases between January and September 2017. There also appears to be a growing trend of individuals and groups aligned with the former ruling party to file reports against any Facebook comments critical of the government to be deemed as offensive or hurtful. The use of the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 (PPA) also remains common in banning publications, and to the list of banned publications continue to grow longer. Suaram therefore continues to call for the repeal the Sedition Act, Section 233 of CMA, the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984, as well as to implement a new law on cyber harassment and online bullying.

Regarding freedom of religion, the main issue that remains unresolved despite promises made by the previous government concerned unilateral conversions of minors. There were a number of reported cases of unilateral conversions by state authorities in 2017. Intolerance against minority sects or interpretations of faith is also an existing concern. Religious authorities have taken action against these groups as they are considered deviants.

In the lead-up to GE14, voter registration was a major concern as registration problems and systematic abuse against legitimate registration of new voters continued. There were also irregularities in electoral roll, with phantom voters and deliberate transfer of voters persisting in 2017. The biggest obstacles to free and fair elections nonetheless would be political financing and corruption.

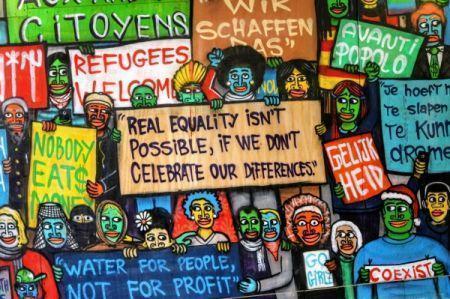

Dealing with refugees and asylum seekers was also a huge challenge during year 2017. There is still no form of legal protection for refugees and asylum seekers, and recognition of their status in Malaysia since Malaysia has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention. However, Malaysia remains an attractive country particularly to the Myanmar Rohingyas fleeing from persecution. Access to education remains a main issue for them since children of refugees and asylum seekers are often denied access if they were not otherwise supported by civil society organisations. Refugees and asylum seekers are also denied the right to work in Malaysia because the UNHCR card is not recognized as a legal document for employment. The previous Malaysian government has taken initatives to register them under UNHCR to help improve their protection and livelihood, however governmental efforts remain limited and even contradictory. This has led to scepticism by civil societies and the Rohingya community in Malaysia. Furthermore, there has also been reports of custodial deaths in immigration detention centres.

In respect of gender and sexuality, the establishment of the Penang Transgender Committee aimed at studying the situation of transgender people in three main areas (i.e. arrest and detention, access to healthcare services, and access to public facilities) is laudable. However, many restrictions and challenges remain particularly in terms of laws and policies such as under Sections 377A and 377B of the Penal Code, which has been interpreted to criminalise homosexual intercourse as ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’. The transgender community also continue to face much difficulty in changing their names and gender in legal documentation as well as violence and discrimination that render them unable to live and work as ordinary citizens with equal rights. Three cases of murder of transgendered women were reported in 2017. Human rights defenders of the LGBT community have also been targeted.

The biggest concern with indigenous people’s rights remains in relation to customary land as the Malaysian rainforest and natural homes of Orang Asal continue to be reclassified as “forest farms”, enabling total deforestation that affects larger and larger areas each time. In response, Suaram expressed a push towards the creation of a ministry for indigenous people to deal with issues that persistently affect them.

Finally, in relation to death penalty, Suaram highlighted that despite amendments to remove the mandatory death penalty under Section 39B DDA in November 2017, 19 people were still executed between 2016 and 2017 without any information relating to the execution made public. Furthermore, no guarantees or initiatives to remedy or re-sentence those on death row pursuant to Section 39B have been made since.

As most of these issues continue to arise, the new government should take swift and concrete action towards addressing them, especially in line line with their human rights promises under their manifesto to abolish mandatory death penalty; repeal oppressive laws (e.g. Sedition Act, POCA, and PPA) and draconian provisions (e.g. under CMA, SOSMA, and POTA); restore and guarantee freedom of the media; fully implement the National Human Rights Blueprint and proposals under the 2013 SUHAKAM National Inquiry Report on Indigenous Land Rights; increase legal protection for women’s rights ; and ratify international human rights conventions (e.g. ICCPR). In particular, SUARAM adviser, Kua Kia Soong, said during the launch event that the top priority for the new government within its first 100 days in power should be dealing with the loss of life in police custody and shootings, as well as in repealing and calling for moratorium on death penalty while the relevant laws are being reviewed.

However, after 100 days in government and conclusion of the first parliamentary session since GE14, none of what was promised under the Pakatan manifesto in terms of human rights have yet to be realised other than the repeal of the Anti Fake News Act 2018, which was hurriedly passed in 2 April 2018 and would have further curtailed freedom of expression. Efforts to initiate institutional reforms have begun but there is already some indication of reluctance in delivering some of these human rights promises and reasons for concern on whether they would be implemented at all. Investigations under the Sedition Act and CMA continue, most notably in the case of lawyer Fadiah Nadwa Fikri, while bills purportedly necessary to replace the Sedition Act such as the Religious and Racial Hatred Bill (which are not unprecedented, remember the National Harmony Act?) are in the pipeline. State action and public response to the child marriage case in Kelantan could only be best described as lukewarm. Despite promising to free the electoral process from government actors and use proposals by relevant CSOs such as BERSIH as reference for electoral reforms, the Electoral Reform Committee created on 16 August 2018 is still not a parliamentary select committee. Nevertheless, with about three years to go before GE15, one remains hopeful and cautiously optimistic.

For further discussions on the new government’s performance of its own human rights promises after 100 days, do join MCCHR-KPUM’s “Let’s Talk Child Marriage and PH Promises on Human Rights” UndiMsia!RCChat this Friday, 24 August 2018, 8pm at PusatRakyatLB. SUHAKAM Commissioner Mr. Jerald Joseph, Yayasan Chow Kit founder Dr Hartini Zainuddin, HAKAM Sec-Gen Mr. Lim Wei Jiet, and Kg Tunku assemblywoman YB Lim Yi Wei will host the groups in this World Cafe event.