This was originally written as a guest post for a blog and has since been edited further. Note: spoilers abound.

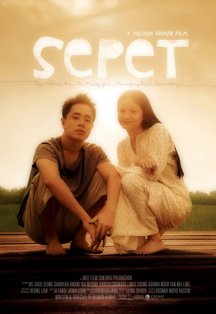

In 2004, the late Yasmin Ahmad, famous for her Petronas advertisements which depicted multi-racial Malaysia released the movie Sepet to much controversy and praise. It won a string of foreign film awards, a legion of fans local and abroad but was also lambasted by certain quarters who felt that the movie threatened the moral fabric of Malay/Muslim life in Malaysia by showing its Malay female protagonist “betray” her bangsa (race) by falling in love with a “kafir” (infidel) [1].

Sepet centers on the relationship between Orked (Sharifah Amani), a teenage Malay girl who had just graduated from secondary school and Jason (Choo Seong Ng), a pirated VCD peddler. This was followed up with Gubra in 2006, which tells the life of an older Orked who was now married; and in 2007, Mukhsin, the prequel which depicted Orked’s childhood in a sleepy Kuala Selangor kampung (village). All these 3 movies made up the “Orked trilogy.”

Orked marks a departure from the typical heroines we see in Malay films. Unlike most Malay women we see on screen, Orked represents a refreshing take on what it means to be a young Malay woman in Malaysia which is a rapidly modernizing country that has to delicately deal with globalization and also the paradox of a multi-racial society, still raw from the May 13th 1969 racial riots.

As Khoo Gaik Cheng notes in her book Reclaiming Adat: Contemporary Malaysian Film and Literature:

“Socio-economic forces, state-initiated, and the cultural development of the NEP years (National Economic Policy 1971-90) had produced a burgeoning discourse about subjectivity among the children of the NEP themselves: what is it like for urban Malay women and men to be both modern and Muslim?”.

And in his review of Mukhsin, Michael Sicinski wrote:

“… transnational feminist theorists would do well to examine Ahmad’s work, since like them, Mukhsin is about complexifying the world, deepening interconnections, delving into the messiness of the conundrums that women face, and moving outward, forging even more connections.” [2]

In Sepet, we are introduced to Orked, who is around 17 years old, living in the mining town of Ipoh, patiently waiting for her Malaysian Certificate of Education results (end of secondary school examinations). She spends her free time indulging in her Japanese movie star Takeshi Kaneshiro obsession, her love for movies by Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wai as well as reading up on a variety of intellectual works. She goes out with friends and does what girls her age usually enjoy.

She is independent, free-spirited and unapologetically opinionated. In one scene with her best friend, she argues passionately about the racist legacy of colonialism, whereby people still fall in love with white people thinking that they are superior, yet as she quips, “You like what you like lah!”

Though still subjected to curfew and the occasional concern from her parents, Orked is largely let to be who she is. In fact, Orked’s parents themselves do not present themselves as “typical Malays”. They enjoy a very sexual life together, unabashed about their affections. In one endearing scene, clad in just sarongs, they dance together in their house to Thai music, while feeding each other fruits. Perhaps their “liberal” attitudes explain Orked’s personality.

We see this further in Mukhsin, In one scene, a neighborhood girl teases young Orked about her father doing domestic chores, causing Orked to snap, “My dad helps in the kitchen because he loves my mother!”

Young Orked refuses to play dolls and weddings, and instead cocoons herself in her room reading books or being out in the fields asserting her right to play with the village boys. Thus, in her films Yasmin Ahmad presents gender roles as unimportant- the absence of which thrive true love and strong character. She also shows the importance of one’s upbringing in shaping one’s worldviews.

Furthermore, Yasmin Ahmad was unapologetic about showing variety of ways Islam is practised. Instead of portraying Orked’s liberal attitude as in direct conflict with Islam, Yasmin Ahmad portrayed Islam as co-existing with so-called “non-Malay” lifestyles. In other words, there’s no singular way of being a Muslim. After all, Islam is not static and devoid of external influences. Khoo notes that: “‘Islam participates in modernity as a globalizing force as well” [3].

Orked gleefully indulges in her pop star obsession as much as she willingly reads the Qur’an after Maghrib (evening) prayers. There is no dichotomy of good Malay woman/bad Malay woman usually portrayed in Malaysian cinema and television, whereby typically the female protagonist after indulging in “bad Western activities” (e.g. smoking, clubbing, fooling around sexually, dressing very scantily) ultimately repents on the prayer mat, or gets punished by society – or both.

Yasmin Ahmad’s Orked is powerful. She defines for herself what her identity should be. She enters into a relationship with Jason, with all the passion and innocence of a 17-year-old girl. A fellow Malay guy friend makes fun of their relationship, denouncing her as a traitor to her race, yet she boldly fights back by saying that: “For generations, Malay men have been marrying outside their race,” hence asserting her sexual right as a Malay woman to do the same. Ironically, she is almost raped by the guy’s best friend, an outwardly respectable young Malay man adored by Orked’s parents. In Gubra, we see Orked now married not to Jason but a Malay man who ultimately cheats on her. Orked’s husband, upon being discovered of his extramarital affair, tries to soothe Orked by saying that the other woman is stupid, and not worth bothering over as she means nothing to him. Orked retorts, “That’s the problem with you Malay men, you think women are stupid!.” This is both a powerful female assertion of her sexual rights and a scathing critique of Malay/Muslim patriarchy. Grief-stricken, Orked leaves her marriage.

But despite the conflicts Orked faces, she also has abundant class privilege. Her parents speak fluent English and they employ a maid. Perhaps most strikingly, Orked has Malay/Bumiputra privilege. As Sepet unfolds, we see that Orked gets 5 A’s for her examinations yet she is awarded a scholarship to study in the United Kingdom, yet Jason scores 7 A’s and fails to get a scholarship, having to work instead illegally by selling pirated VCDs. Thus, Yasmin Ahmad shows the contradiction Malay women in Malaysia face: on one hand, they have to battle gender roles imposed on them, and yet Bumiputra privileges mean that in some ways, they are able to sail through life. Thus, it is crucial to examine the factors of class and ethnicity further when examining Malay womanhood.

All in all, through her “Orked trilogy”, Yasmin Ahmad has provided an interesting glimpse of the multi-faceted nature of Malay womanhood. Unlike the typical representation of women in Malaysian cinema and television, Yasmin Ahmad has managed to construct a different way of seeing young Malay women in Malaysia. In her beautiful Orked trilogy, the late Yasmin Ahmad showed that Malay women face multiple contradictions yet manage to deal with them with intelligence and resilience.

Reference

[1] Al Amin, FAM 2008, ‘Controversies surrounding Malaysian independent female director Yasmin Ahmad’s first film Sepet’ in Proceedings of the 17th Biennial Conference of the ASAA, Melbourne, Australia, Monash University, pp. 1-12

[2] Sicinski, M 2008, Reviews of new releases seen, August 2008, The Academic Hack, viewed 10th April 2009.

[3] Khoo, GC 2005, Reclaiming Adat: Contemporary Malaysian Film and Literature, UBC Press, Vancouver.