Chris Hooper analyses treason and capital punishment in the context of India and Malaysia.

Societies are best judged in how they respond to the most egregious examples of criminality. How do those whose conduct has so raised the ire of the community that many wish them to suffer? It is in these situations that the humanity of our society is truly tested. Many would extol the virtues of a fair trial in general, but would happily see these basic tenets of a humane legal system turfed in extreme cases. For this reason, the authorities that purport to represent the people must provide for a system of legal rules and practices which ensure that even those most despised by society are treated fairly and tried according to the rule of law. Society as a whole must be better than the individuals desire for retribution which often takes sway following egregious cases of criminality.

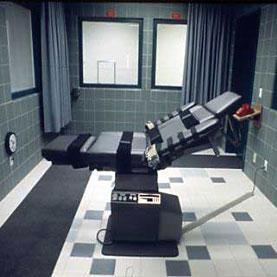

This is demonstrated most emphatically in cases involving treason or waging war against the government of the day. Treason in its various forms has long been a capital offence in many societies. It may be proscribed for by statute, or in some cases, under religious law, such as for the hudud crime of rebellion (or ‘baghy’).[1] In common law systems such as Malaysia and India, hanging is the most commonly utilised method of execution.

The trials which commonly accompany these high-profile cases provide a rare insight into how a society’s claims to have an open and fair justice system play out when it is truly tested in these rare and extreme examples of criminality.

This paper will examine two high-profile cases brought under commensurate legislative provisions in India and Malaysia. Section 121 of both countries’ Penal Codes provide for the crime of Waging War against the Government (or King, as is the case in Malaysia). In both cases, the courts have constructed this section requires that a person be shown to have engaged in acts which amount to the ‘waging of war’ and that those acts must be directed against the ‘Government’ or ‘King”.

India: the Kasab Case

The devastating attack on Mumbai in 2008 by 10 Pakistani members of the Lashkar-e-Toiba hit 5 locations around the city including the famous Taj hotel and left 164 people dead. One of the 10 militants who made landfall at Badwar Park was Ajmal Kasab. The group of which he was a member orchestrated the attack with the aim of weakening the Indian State and achieving independence for Kashmir, a province in the North of India. While the plan was ultimately unsuccessful, it left a lasting impact on the country and its people, and Kasab’s trial in the Bombay Supreme Court provides a very recent and topical insight into India’s capital punishment regime in cases of treason.

In India, treason (i.e. ‘waging war against the Government of India’) is a capital offence under s 121 of the Penal Code, but formed only one of the 86 charges levelled against Kasab. However, this paper will only focus on the charges under s 121. Furthermore, it will address only those arguments raised by Kasab’s legal team raised in an attempt to avoid capital punishment for their client as death is a discretionary sentence under s 121. Of these, the primary arguments focused on whether or not Kasab’s conduct ought to be viewed in isolation or as part of a larger conspiracy, and whether sufficient mitigating factors existed so as to justify a commutation of his death sentence to life imprisonment.

Treason and Conspiracy

Despite objections by the appellant, the Indian Supreme Court admitted into evidence transcripts of telephone conversations between the militants holed up in the Taj Hotel and their handlers in Pakistan in relation to the movements of the security forces and the best course of action for the attackers in carrying out their plan. Despite the fact that Kasab was already in police custody at this point, the court held that the conversations related to a plan which Kasab had helped to hatch in Pakistan and which he was directly engaged in carrying out at the time he was arrested. It was therefore admissible to establish a connection between his actions and the larger conspiracy of which he was a part.

For the Court, this connection to a larger plan was sufficient to turn Kasab’s attack on the central railway station in Mumbai from an isolated terrorist attack into an act of waging war against the Government of India. Even though his target was not a government building, the court held that ‘‘government’ was equated interchangeably with the people who vest legitimacy to govern in the representatives of the State and the State itself. Therefore, systematically attacking the people of India as part of a larger insurgency was sufficient to constitute an attack on the government of India.

The Court then considered the presence or otherwise of any mitigating factors to justify a commutation of the death sentence. The Court declined to take account of the fact that Kasab had left school at a very young age, had a difficult family background, and had clearly been brainwashed by a group he initially believed to be seeking peaceful social ends. It held that his age was the only mitigating factor, and this alone was insufficient to justify and commutation given that he demonstrated no remorse and was found to be beyond any attempt at rehabilitation.

The Court explained that while it agreed with earlier decisions in which it was held that the death penalty should be reserved for only the ”rarest of rare cases when the alternative option (of life sentence) is unquestionably foreclosed”’[2] cases, the manner in which Kasab committed his murders, his motivations of killing, the anti-social and abhorrent nature of his acts, the sheer magnitude of his crimes, and the indiscriminate nature in which he selected his victims made death the only appropriate penalty. It said that if any case were to attract this harsh penalty, then it must surely be this one. It continued, “to hold back the death penalty in this case would amount to obdurately declaring that this Court rejects death as lawful penalty even though it is on the statute book and held valid by Constitutional benches of this Court.”[3]

Kasab was ultimately convicted and put to death by hanging at Yerwada Jail in Puni on 21 November 2011, after several appeals and accusations of police corruption particularly related to his confession were made before the judicial magistrate shortly after his arrest. It was alleged that the confession was partially fabricated by the police in order to suit the outcome of their investigation and to fill the holes in the prosecution’s case theory. This argument was rejected by the court, and Kasab was hanged in secret at 7:30am, before being buried at an undisclosed location.[4]

Malaysia: Al-Maunah – Martial Arts Group Turned Armed Insurgents

In Malaysia, an attempt was also made to overthrow the government of the day and install an Islamist regime in its place. In July 2000, a group known then as Al-Maunah began its existence as a martial arts training group but quickly morphed into a religious cult, believing that their leader had supernatural powers. It leader, Mohd Amin Mohd Razali along with 28 co-conspirators, conducted raids on army facilities with the assistance of a then-Army Major who was assisting the group’s plans.

The group set up a base in Bukit Janilik and began conducting training exercises with their stolen weapons. These unusual sounds alerted locals who informed the authorities, leading to the establishment of a cordon around the area by security forces. Prior to this, the group launched attacks on the Carlsberg brewery at Shah Alam, the Guinness and Anchor brewery at Petaling Jaya, and the Hindu temple at Batu Caves; however, they met with only limited success.

Despite this, three people were killed as a result of the group’s activities, including a police officer, army private and a civilian who stumbled on the group’s camp while he was out picking durian fruit.

While 29 individuals were charged in connection with these acts, this paper looks only at the capital punishments handed down with respect to the group’s leader and his three lieutenants. All three convictions were upheld on appeal,and Razil was hanged on 4 August 2006 in Selangor. Zahit Muslim, Jamaluddin Darus, and Jemari Jusoh were hanged a week earlier.

The legal discussion in this case was smaller in volume than that discussed in the Indian case above. Argument initially focused on the weight of the burden of proof which fell upon the prosecution in cases such as this. given that all parties agreed the facts fell within the ambit of the Essential Security Cases (Amendment) Regulations 1975, reg 2(2) and 3(1). A majority of the Court held that the effect of these regulations was to remove the normal requirement for the prosecution to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt, and only require the court to call on the defence to make its argument at the close of the prosecution case if the prosecution has first established a prima facie case against the accused. On this basis, the appellant’s call for the convictions to be set aside on the basis of a miscarriage of justice was rejected.

The Court moved on to consider the appropriateness of an appeal against sentence, but unanimously declined to hold accordingly on the basis that although it accepted Indian authority (without explaining which cases the decision here was based upon) standing for the proposition that capital punishment should be reserved for only the most serious crimes, the acts of the accused fell within that category of offending.

As the first and so far only case involving s 121 of the Penal Code in Malaysia, the court had the opportunity to clearly enunciate the legal principles which govern cases of this nature and also to explain its reasons for exercising its discretion in favour of the death penalty here. It declined to do this, however.

Comparison and Analysis

The subject matter in both cases was of course highly sensitive. India’s relationship with Pakistan in relation to possession of the states which lie along the borders between the two countries has been the source of both political consternation and, tragically, armed conflict on both sides. Likewise, the appropriate role of political Islam in Malaysia and the status of Islamic law routinely captivate headlines across the country and is a highly divisive issue.

It is also true that the Malaysian case could have easily escalated, leading to a greater number of deaths and drastic consequences for the government and society generally.

However, it is also true that both cases were driven largely by religious extremism. Particularly in the Malaysian example, many of the militants were willing to surrender without a fight with the army. Indeed, 10 of the militants who were detained under the then-Internal Security Act were later released under supervising having established that they were not longer a threat to society. If the purpose of capital punishment for treason offences is to deter others from similar conduct in the future, a more powerful message of deterrence may have come from the rehabilitation of the ring-leaders who would eschew their previous conduct. This would take the wind from the sails of people who might seek to follow in their footsteps in the future. De-radicialisation has proven effective, particularly in cases involving young men who have been subjected to a one-sided interpretation of scripture by an extreme teacher.

Following the recent publication on Malaysian attitudes to capital punishment by UK-based NGO, the Death Penalty Project, there appears to be a growing willingness on the part of Malaysians to re-open the death penalty debate and consider the appropriateness of capital punishment based on the specific circumstances of accused persons.

Mounting pressure from civil society, coupled with a willingness on the part of the government to look at this issue, may allow us to ignite discussion based on case studies like those outlined above. On the surface, attempts to overthrow the government of the day constitute one of the more serious crimes on the statute books. However, if we consider the ideological misinformation upon which many militants in extremist groups operate, a more humane approach based on de-radicalisation and open dialogue, coupled with harsh prison sentences and rehabilitative mechanisms, may actually paint the government in a better, more legitimising light than simply hanging the perpetrators and seeking to make the problem go away by capital means.

While there would be some who will undoubtedly view this argument as being soft on the most serious iterations of crime, evidence suggests that the retributive motivations for capital punishment exist alongside a deeper desire to understand why people would engage in conduct like this. Showing that many of the perpetrators are acting on what can only be described –in the Malaysian example at least — as misguided and poorly thought-out interpretations of religious texts may allow for a deeper understanding of what motivates actions of this kind.

Regardless of a person’s attitude towards capital punishment, it seems hard to justify the killing of a person who’s actions are driven by misinformation and supported only by a cult of personality.

If society is to be judged on how it treats its most vulnerable individuals, cases of this kind surely give us moment for consideration of these deeper questions.

[1] Elizabeth Peiffer, ‘The Death Penalty in Traditional Islamic Law as Interpreted in Saudi Arabia and Nigeria’ (2005) 11 William and Mary Journal of Women and the Law 507.

[2] Kasab Case at 585.

[3] Ibid.

[4] ‘Ajmal Kasab Hanged and Buried in Pune’s Yerwada Jail’, Times of India (2012) 11 November.

Featured image from Scientific American