A version of this article was originally published in the Sunday Star and on the author’s website.

The January 2nd raid by the Selangor Islamic Affairs Department (Jais) on the premises of the Bible Society of Malaysia (BSM), in which 331 copies of Malay and Iban Bibles were seized, has brought to national attention a piece of state legislation hitherto unknown to many Malaysians – the Non-Islamic Religions (Control of Propagation Amongst Muslims) Enactment 1988 of Selangor (Selangor Enactment).

So far, Jais has argued they were empowered to do so under Section 9 (1) of the Selangor Enactment, which prohibits any non-Muslim to use in writing or speech any of 25 words or any of their derivatives and variations, as stated in Part 1 of the Schedule, pertaining to a non-Islamic religion.

The 25 words are Allah, Firman Allah, Ulama, Hadith, Ibadah, Kaabah, Kadi, Ilahi, Wahyu, Mubaligh, Syariah, Qiblat, Haj, Mufti, Rasul, Iman, Dakwah, Injil, Salat, Khalifah, Wali, Fatwa, Imam, Nabi andSheikh.

Section 9 (2) also prohibits a non-Muslim to use 10 expressions of Islamic origin set out in Part II of the Schedule, including Alhamdulillah and Insyallah.

Non-Muslims can, however, use the words and expressions by way of quotation or reference.

Jais contended that Section 9 (1) had been contravened because the Malay and Iban Bibles contain the word “Allah”. Further, they were entitled to arrest without warrant the BSM chairman, lawyer Lee Min Choon, and manager Sinclair Wong as section 11 provides that all offences and cases under the Selangor Enactment are deemed to be seizable offences and cases under the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC), that is, offenders of seizable offences can be arrested without any warrant of arrest.

A fortiori, as this is a law passed by a state legislature, it has the force of law and quite rightly it can, therefore, override the 10-point solution decided by the Federal Cabinet and communicated via the Prime Minister’s letter dated April 11, 2011 to the Christian Federation of Malaysia.

Apart from section 9, the Selangor Enactment also makes it an offence for any non-Muslim to:

- influence or incite any Muslim to change his faith (Section 4);

- subject any Muslim minor to influences of a non-Islamic religion (Section 5);

- approach any Muslim to subject him to any speech on or display of any matter concerning a non-Islamic religion (Section 6);

- send or deliver any publications concerning any non-Islamic religion to a Muslim (Section 7); and

- distribute in a public place any publications concerning a non-Islamic religion to a Muslim (Section 8).

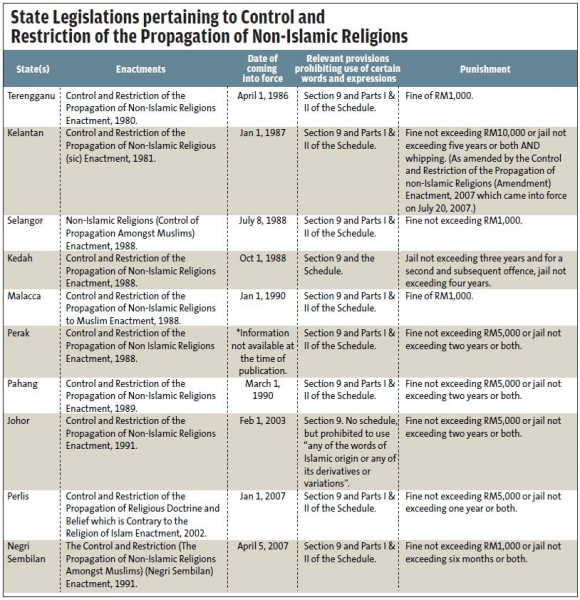

To date, 10 states have passed similar enactments with almost identical provisions except for the penalties and the words and expressions stated in the Schedule (see the table). Effective July 20, 2007, Kelantan has imposed the most stringent punishment, which includes mandatory whipping for all offences. The Johor State Enactment does not contain any schedule, but it imposes a blanket ban on the use of any “words of Islamic origin”.

There is no equivalent federal law for the federal territories except for section 5 of the Syariah Criminal Offences (Federal Territories) Act, 1997 (Act 559) which makes it an offence for any person to proselytise a Muslim to a non-Islamic religion. Act 559 has no similar provision like section 9.

In fact, in October 1999, then Terengganu Mentri Besar Datuk Seri Abdul Hadi Awang, who was also Marang MP, tried but failed abysmally to move a private member’s bill titled the Control and Restriction of Propagation of Non-Muslim Religions (Federal Territories) Bill at the Federal parliament.

It is interesting to note that the attempt received vociferous opposition from Barisan Nasional parliamentarians, especially the non-Muslims. This was rather a risible response because, at that time, similar enactments had already been passed in nine states (other than Perlis), including those governed by Barisan unless the non-Muslim state legislators had been caught unawares.

To the best of my knowledge, only one person has been prosecuted and convicted under such law. Krishnan a/l Muthu was charged in 2002 and convicted under Section 4 of the Pahang State Enactment for trying to convert a Muslim to Hinduism and was fined RM1,500 and jailed for 20 days [Public Prosecutor v. Krishnan a/l Muthu (Magistrate Case No. MA-83-146-2002)].

Further, no such similar enactment has been passed in Penang, Sabah and Sarawak. However, a fatwa with regard to certain words being exclusive to the Muslims may have been issued under section 48 of the Administration of Religion of Islam (State of Penang) Enactment 2004 but it does not bind non-Muslims.

Generally, non-Muslims have no problem with sections 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 because the offences deal with a non-Muslim’s specific acts of propagation to a Muslim. They only take issue with section 9 because the offence has been created without any act of propagation whatsoever by a non-Muslim. In other words, by law, certain words and expressions now belong exclusively to the Islamic religion. There is no problem if such words are indeed not used by other religions. Conflicts have now arisen over the use of the word “Allah” because Bahasa Malaysia speaking Christians and Sikhs also use it to describe their God.

Hence, the constitutionality of section 9 has been called into question in that the relevant state legislatures have no competency to enact section 9 for the following reasons:

1) Article 11(4) and Paragraph 1, List II of Schedule 9 of the Federal Constitution only allow states to pass law to control or restrict the propagation of any religious doctrine or belief among Muslims. To put it in another way, Muslims may propagate the Islamic religion to non-Muslims but not vice versa. But the states do not have the power to make laws controlling or restricting, let alone prohibiting, the use of certain words and expressions without any act of propagation.

In other words, a state law can only be enacted to proscribe a Christian from delivering a Bible which contains the word “Allah” to a Muslim, and not if the former uses the same Bible for his own personal belief.

2) Section 9 is also contrary to Articles 3(1) and 11(1) which confer on every non-Muslim the fundamental right to profess and practise his own religion in peace and harmony. Article 11(3)(a) states that every religious group has the right to manage its own religious affairs. A Malaysian’s right to freedom of religion is further entrenched under Article 12(3) which provides that no person shall be required to receive instruction in or to take part in any ceremony or act of worship of a religion other than his own.

3) It is also against a person’s right to freedom of speech under Article 10. As regards whether Parliament can restrict the right to freedom of expression over the use of such words on the grounds of national security under Article 10(2)(a), reference can be made to the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Jamaluddin Bin Othman [1989] 1 CLJ Rep 109 (“the Joshua Jamaluddin case”).

In that case, Jamaluddin was detained under the repealed Internal Security Act, 1960 on the ground that he had participated in a work camp and seminar for the purpose of spreading Christianity and, as a result, converted six Malays to Christianity.

The High Court ordered his release. When the matter went up for appeal to the then apex court, the Supreme Court, Chief Justice of Malaya Tan Sri Hashim Yeop Sani said:

“We do not think that mere participation in meetings and seminars can make a person a threat to the security of the country. As regards the alleged conversion of six Malays, even if it was true, it cannot in our opinion by itself be regarded as a threat to the security of the country.”

4) Article 4 (1) upholds the supremacy and paramountcy of the Constitution in that any law which is inconsistent with it shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

Having said that, Section 9 is still a valid law unless repealed or amended by the respective state legislature. In the alternative, anyone can challenge its validity but he must first obtain leave from a Federal Court judge under Article 4 (4) unless the challenge comes from the federal or state government.

It is now apposite to point out that under Paragraph 1, List II of Schedule 9 of the Constitution, the Syariah courts have no jurisdiction over non-Muslims. It follows the CPC shall apply in the arrest of any non-Muslim under the State Enactment.

This is correctly reflected in section 11(5) of the State Enactments of Johor, Pahang, Perak and Negri Sembilan and section 12(5) of the Kedah State Enactment in that anyone arrested under these State Enactments must, without unnecessary delay, be handed over to the police or taken to the nearest police station and the provisions of CPC shall apply.

Similarly, as all the State Enactments do not have any express provision relating to search and seizure and because only CPC has application to non-Muslims, it is illegal for Jais to enter BSM’s premises and seize the Bibles without first having obtained a warrant of search from a magistrate under Section 56 of the CPC.

I must hasten to add that no non-Muslim can be charged in a Syariah court. He has to be prosecuted in a civil court. If he is to be charged in a civil court, then only the Attorney General will have a say in the prosecution under Article 145(3) of the Constitution. If he is charged or convicted or jailed by a Syariah court, then the non-Muslim offender is entitled to seek remedy from the civil court under section 25(2) and the Schedule of the Courts of Judicature Act, 1964 which empower the civil High Court to grant various orders including the writs of habeas corpus and prohibition (see Abdul Rahim bin Haji Bahaudin v Chief Kadi, Kedah, [1983] 2 MLJ 370, HC.)

The above explains my opinion of the legality of the JAIS raid. But frankly, I do not think the Allah issue can or should be resolved through the courts. In terms of enforcement, the hard copies of the Malay and Iban Bibles can always be seized, but the soft copy is still easily available for download through the Internet. It is, of course, axiomatic that Pakatan state governments should also observe the 10-Point Agreement albeit Barisan-controlled states are expected to do so.

If our founding fathers could set aside their differences and achieve independence through social consensus, I see no reason why current political leaders from both divides do not have the same political will and gumption to come to grips with an issue which has now threatened our national cohesion.

Perhaps if we only had a royal council of inter-faith leaders akin to the presidential council set up under the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act of Singapore, it may be the way out of this religious stalemate.

See also:

Nice writing, please follow me to find the Best Indian astrologer in detroit

great

Nice!