Zijian talks about why the Sedition Act is hardly relevant to our current times.

Yes, we all know it’s going to be election time and the whole nation is high on the election fever. This springs to mind a promise made on Malaysia Day last year. Can it be honoured in time?

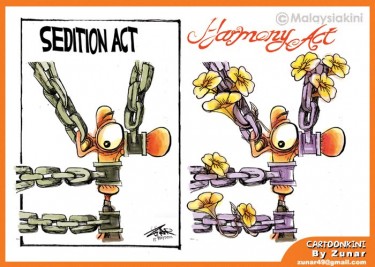

When I was a little kid, naïve and innocent, we were introduced to the notion that the government isn’t as good as it should be. As I grew older and started to talk about national topical issues, I was reminded by my parents and grandparents to keep quiet on these matters, for I could be apprehended. Heck, they even frightened me with our Sedition Act 1948 – soon to be replaced with, but not yet, by the euphemistic “National Harmony Act”.

In the dawn of the Malayan Emergency, the Sedition Act 1948 was enacted – along with a string of other draconian laws – to combat communists. While only intended to protect the nation from communists and their sympathisers, its usage declined drastically when the Malayan Emergency ended in 1960, but was still around as communism had not been fully curbed. Subsequently, the use of this Act should have come to an end when Chin Peng and gang finally came out from the lush jungles of Malaya bordering the Thai frontier to surrender in tandem with the fall of the Communist bloc in Europe to sign the Hatyai Peace Accord 1989. (Note: The peace accord came about only two years after Ops Lalang, where many politicians from both sides of the fence were detained for allegedly inciting racial riots).

But hell no, this Act, along with many others, was not repealed. Sixty-five years on, the Act is still in force. Further adding salt to the wound, it was amended by the Emergency Ordinance 1971 – not long after the May 13th riots in 1969 – to criminalise any questioning on Part III (on citizenship), Article 152 (on national language), Article 153 (on the special position of Malays, along with Sabah and Sarawak) and Article 181 (on Ruler sovereignty) of the Federal Constitution. Now, it would appear that the ‘May 13th fear’ is the purpose of retaining this Act. Deviated from its initial purpose, it’s now an arbitrary tool of oppression by individuals with vested interests – curtailing the famous Article 10 of our Federal Constitution.

The Prime Minister announced last July that the Sedition Act 1948 would be repealed and replaced with a new statute – the National Harmony Act. What? A replacement statute? This isn’t the first time!

Remember, remember, the SOSMA for the ISA, which drew much flak from many quarters. Many have called it purely cosmetic. Seems like our big boys up there are not getting the crux of the problem, eh? While the ruling coalition has honourable individuals who deserve the well-earned respect of the people, most are the opposite (or they pretend to be s0). Sure, we all know that freedom of expression comes with facts and figures, not emotions and hatred – which was also probably the other reason the Sedition Act 1948 was enacted. But has this been honoured? No. It has become a creature of arbitrariness.

Interestingly, throughout its implementation, very few politicians from the ruling government were charged under this Act. The only notable one was Mark Koding (I’m sure many have not heard his name), an MP who talked about the abolition of Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools. Conversely, the Act has been invoked against many opposition politicians. Many of us know the high profile case against Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng, once the MP for Kota Melaka in Melaka. He was charged under Section 4(1) (b) of the Act for causing ‘disaffection with the administration of justice in Malaysia’; he accused the Attorney-General for not bringing charges against the (then) Melaka Chief Minister, Rahim Thamby Chik, for statuatory rape, which caused big hoo haa in 1994.

Recently, the infamous Ibrahim Ali – president of the pro-government Malay rights group Perkasa – called for the burning of Bibles in Malay containing the word ‘Allah’. Not much action has been taken other than the police questioning him. More recently, Perkasa and ex-PKR member Zulkifli Nordin were recorded in a video where he mocked the Hindu religion.

The Act itself, if you pick up a copy of it, show very poor draftsmanship – very vague and general in nature, highly contrary to what Acts of Parliament ought to be – detailed, clear, and unambiguous so that judges and lawyers do not have to crack their heads in deciphering Parliament’s intention. It shows how this law can be twisted in favour of individuals with vested interests. A “seditious tendency” is defined in section 3 as follows: to bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against any Ruler or government; to seek alteration other than by lawful means of any matter by law established; to bring hatred or contempt to the administration of justice in the country; to raise discontent or disaffection amongst the subjects; or to promote ill-will and hostility between races or classes.

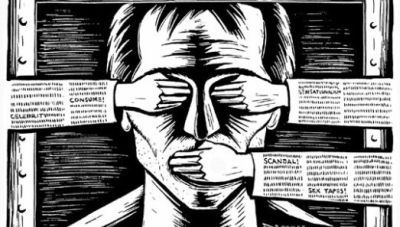

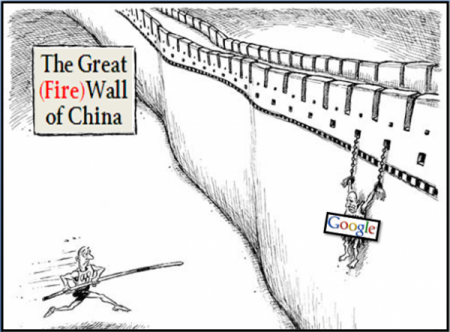

How much hatred or contempt to excite disaffection against any Ruler or government constitutes sedition? Is this contrary to democracy? And shouldn’t a bad government be criticised? It would appear that creativity is curbed – everyone being so afraid to express themselves in fear of being caught by the 1948 Act. There is no doubt that our creative industry has taken a dent from political – and more popularly ‘moral’ – censorship. Local films and plays have shied away from political plots, and while we can count Hati Malaya (1957) as political, we don’t see a movie from the other side of the political divide. While authors have fared better as there is less banning of books than films, they are still not spared. Such is the practice of communistic states like China, not democracies, as our Federal Constitution dictates our nation to be. Thankfully, our internet censorship is limited and restrained unlike in China.

Since the political tsunami in the 2008 General Election, Malaysians have become more politically matured and are more opinionated. Although relatively still a long way to go when compared with other democratically matured countries, it should be acknowledged as a very giant leap forward. The Malaysian population is also more educated than ever, and with the information age, a more rational Malaysian society has been formed. Do we still need this Act to control our mouths and tongues? All these are reasons why the Sedition Act 1948 should not be replaced by another legislation. It’s time we Malaysians openly discuss matters of national importance – not by hate, emotion, or pride – but by facts, knowledge and maturity, and without the Sedition Act 1948, National Harmony Act, or a Race Relations Act (the name suggested before the National Harmony Act was coined, to portray it in a more positive light). Time we forget the dark events of May 13, and embrace in full spirit what Article 10 of our Federal Constitution has stated – Freedom of speech. Do we need old wine in new bottles? Clearly not.

Nice!

I think that you could do with some pics to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, this is great blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.

If that is the case, then why European countries have hate speech laws?