“To some it’s at the the tip of the sharp tongue of satire. To others it’s an example of an attempt at funny going too far.” – BBC Online, October 13th 2008

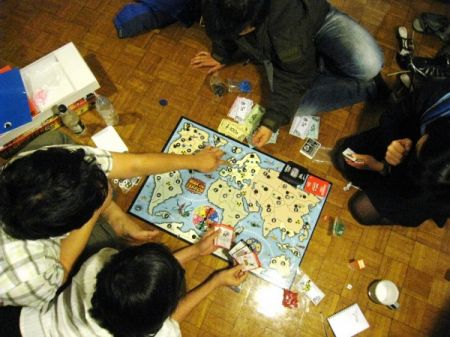

We huddled around the world map, scrutinising a matrix of towns, cities and terrorist camps to decide where best to attack next. We were tired and all we wanted was to end the game. 7 hours into the game, no one was winning.

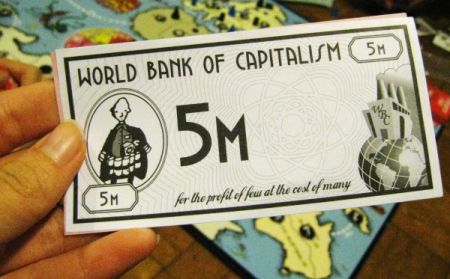

This is the War On Terror, where Empires are built, territories are expanded, terrorists are bought and besieged, whole continents are nuclear bombed and the sole source of revenue is oil. Too sensitive, too politically incorrect, too heavy a topic to be designed into a board game? Games, the creators of the game believe, deserve to mature and assume their rightful place as a vital form of social commentary as much as a source of entertainment. As their manifesto made clear, the fact that an issue is no laughing matter does not mean we cannot have a good laugh and think about it seriously at the same time.

This is rule no. 1 at TerrorBull Games: everything’s game. World politics, environmental catastrophe, life and death… It’s all fun. It’s all fair game. Why should anything be excluded from a game? Are some subjects so hallowed that we can only discuss them in hushed, respectful tones? We don’t believe so. Being ‘hushed’ represses opinion, supresses discussion, interaction, shouting, anger, laughing. Natural human responses.

It’s not every day that you play a game that changes the way you think, that forces you to confront your ideas from a whole new perspective, that nudges you into wondering if the game is real and all reality is a game. A board game that is evidently not designed to make people feel good: “If it makes you laugh and THINK at the same time, it’s going to be a good game. If it provokes you, even better.”

And provoke it did. Take an Empire card from the deck and you may get Radiation Clean-Up (“Kick some dirt over it. Brush the rest under the carpet. In 50 thousand years it’ll be good as new.”). Or if you could draw from the Terrorist cards deck, you’ll get the Terrorist Attack card (“Lock up your civil liberties, the terrorists are here.”). In the second edition of the game there’s a new card called “Civilian Protest” which allows a player to stop a war, if he rolls two dice and gets a score of 13. Go figure.

Cheating, lying and bribery are not allowed; they are highly encouraged. In fact they are part of the instruction itself, on the first page: “In our world there is no black and white. Deception is encouraged, hypocrisy is the norm and the only true ally is money… Confusing and unfair? You bet it is. Luckily, it’s only a game.” (Phew?)

Politics and power play began as soon as we started talking to one another, and the instruction booklet kindly reminded us that creative bargaining includes exchanging cards for jam and toast at 2am. And then there was the Secret Messages pad “for treaties, resolutions and other breakable promises.” We learnt to become transient friends and foes, to break alliances as soon as they were formed. One of us was in a particularly strong position, strong enough to jump ship as he wished, too strong for the comfort of other players. At one point he was about to be brought down by his old allies the Terrorists and turned to his new friends the Empires for cooperation instead:

“Let’s get rid of the Terrorists. They are a big problem.”

“No,” said the Empire player. “You are a big problem.”

Lesson learnt: When you’re in trouble, what friends?

Before the game commenced everyone kept trying to find out how to score points, how many points were required to win, when the requirement changes. What is the objective of the game? How do you win? But after the first 15 minutes no one asked anymore, and no one bothered. Suddenly all we cared was about oil and things spiralled uncontrollably into a world struggle for power.

In the 6th hour we were finally tired enough to decide to figure out how to win the game. By then we were already so deeply drawn into the game, sucked into a bottomless whirlpool of development and demolition, that both sides couldn’t and wouldn’t surrender. It was exhausting; we didn’t really want to win, but we really didn’t want to lose.

After a gruelling 8(!) hours the war on terror was finally over. On the board, according to the game’s rules about scoring points, the terrorists won. But it was clear to us that no one had won, no one was ever winning, because the war was unwinnable in the first place – it has always been. It was almost dawn, and we took a nice long walk to watch the sunrise from a small mound. The feeling was inexplicable: the darkness was over and finally light was coming through once again.

I couldn’t stop wondering about how we were just fighting the war for the sake of fighting the war, not winning it. Luckily, it’s only a game? Wars on terror, on crime, on corruption; endless struggles for freedom, against oppression. Are we fighting for what we’re fighting for because we genuinely believe in our goal, or because we’ve been doing it for so long and we just didn’t want the process to stop? Have we been so engrossed in fighting the war all the while that we never thought about how to end it? The Insurgency Emergency card says “If you fight fire with fire, you’ll end up with two fires.” If for every contentious issue we resort to ‘war’, can the war ever be won? Is it called winning? Does it matter at the end?

When other curious friends repeatedly asked us to join them and play the game again, we all declined, the five of us now united by the impact of a long night. It was no coincidence that on separate occasions each and every one of us gave the same reason: we’re sick of war. We’ve had enough. It will take a long while for us to recover from this before we feel ready to play the game again. No more wars for now.

And then the imperialists and the terrorists went together for breakfast, and together we gratefully embraced a brand new day.

http://fewhacks.com/

You should really check this when you want to peep into someones account of snapchat.